Or, The Equal Opportunity Celebrant – Part 2

Note: Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, some bakeries may have closed, new ones have opened, and prices may vary across the board. The Mid-Autumn Festival, however, will be with us forever – as long as there are autumns to celebrate!

(Click on any image to view it in high resolution.)

A visit to any Chinatown bakery this time of year will reveal a befuddling assemblage of mooncakes (yue bing) in a seemingly infinite variety of shapes, sizes, colors, ornamentation, and fillings, all begging to be enjoyed in observance of the Mid-Autumn Festival. Also known as the Autumn Moon Festival, this important holiday occurs on the fifteenth day of the eighth lunar month (around mid-September or early October on the Gregorian calendar) when the moon looms large and bright – the perfect time to celebrate summer’s bounteous harvest. They’re sold either individually or in attractive gift boxes or tins since it’s customary to offer gifts of mooncakes to friends and family (or lovers!) for the holiday.

The first point to note is that various regions of China have their own distinct versions of mooncakes. A quick survey of the interwebs revealed styles hailing from Beijing, Suzhou, Guangdong (Canton), Chaoshan, Ningbo, Yunnan, and Hong Kong, not to mention Taiwan and Malaysia. They’re distinguished by the types of dough, appearance, and fillings, some sweet and some more savory. In my experience, Chinese bakeries in Manhattan, Brooklyn (Sunset Park), and Queens (Flushing) favor the Cantonese style, but Fujianese mooncakes are easy to find along stoop line stands outside of markets in neighborhoods where there’s a concentration of folks from Fujian.

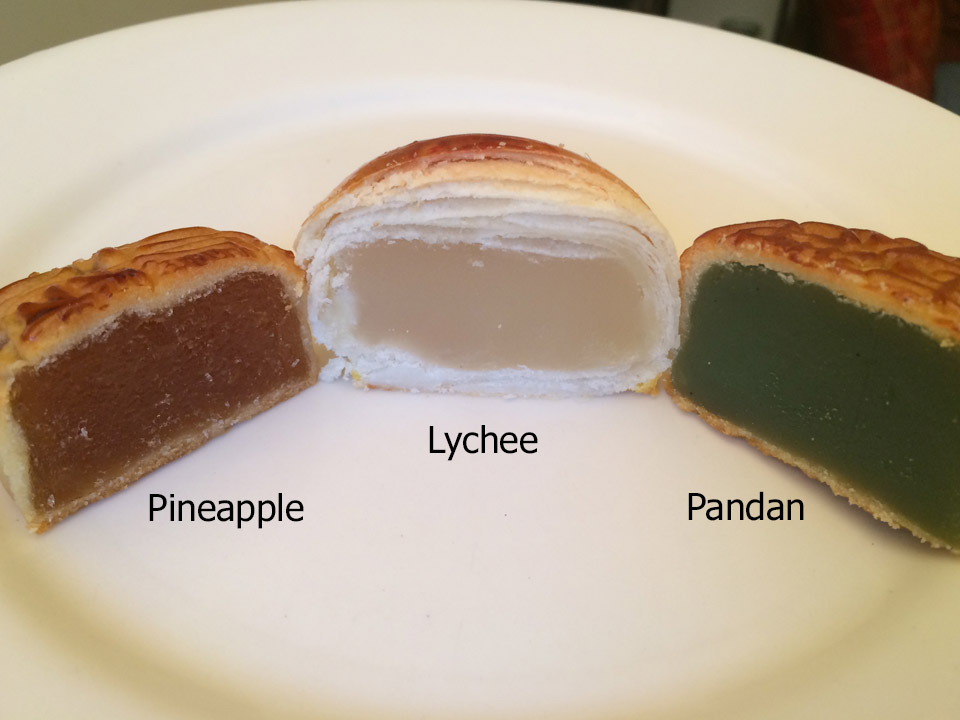

You’ll commonly find mooncakes with doughy crusts (golden brown, soft, somewhere between cakey and piecrusty, often with an egg wash sheen) as well as those with white, paper thin flaky layers that betray lard as a critical ingredient; chewy glutinous rice skins (these aren’t baked); and gelatinous casings (jelly, agar, or konjak), the most difficult to find in the city. Golden-baked, elegantly decorated Cantonese versions are round (moon shaped, get it?) or square, are fluted around the perimeter, and have been created using molds made of intricately carved wood to provide the ornate design or an inscription describing what’s inside (see photo).

Fillings among the Cantonese types are dense and sweet and include lotus seed paste, white lotus seed paste, red bean paste, and mung bean paste, sometimes with one or two salted duck egg yolks (representing the harvest moon) snuggled within. In addition, there are five-nut (or -kernel or -seed) versions, packed with chopped peanuts, walnuts, almonds, pumpkin seeds, and watermelon seeds as well as a variety made with Jinhua ham, dried winter melon, and other fruits buried among the nuts; its flavor was a little herby, not unlike rosemary, but I couldn’t quite identify it. These last two were particularly tasty. All are about 3 inches wide and 1½ inches high and sell for about $4.50–$6 as of this writing; mini-versions are available as well.

A visit to Flushing exhibited all of these as well as some outstanding fruity varieties including pineapple, lychee, and pandan; these can be best described as translucent fruit pastes and are perfect for the novitiate – a gateway mooncake if ever there was one.

Here are two pandan mooncakes, one with preserved egg yolk and a mini version without, from Fay Da Bakery at 83 Mott Street in Manhattan’s Chinatown.

Here are two pandan mooncakes, one with preserved egg yolk and a mini version without, from Fay Da Bakery at 83 Mott Street in Manhattan’s Chinatown.

In another market, I found a white, flaky pastry version, Shanghai style, I believe; the filling was like a very dense cake with a modicum of nuts and fruits providing some contrast and crunch – certainly tasty.

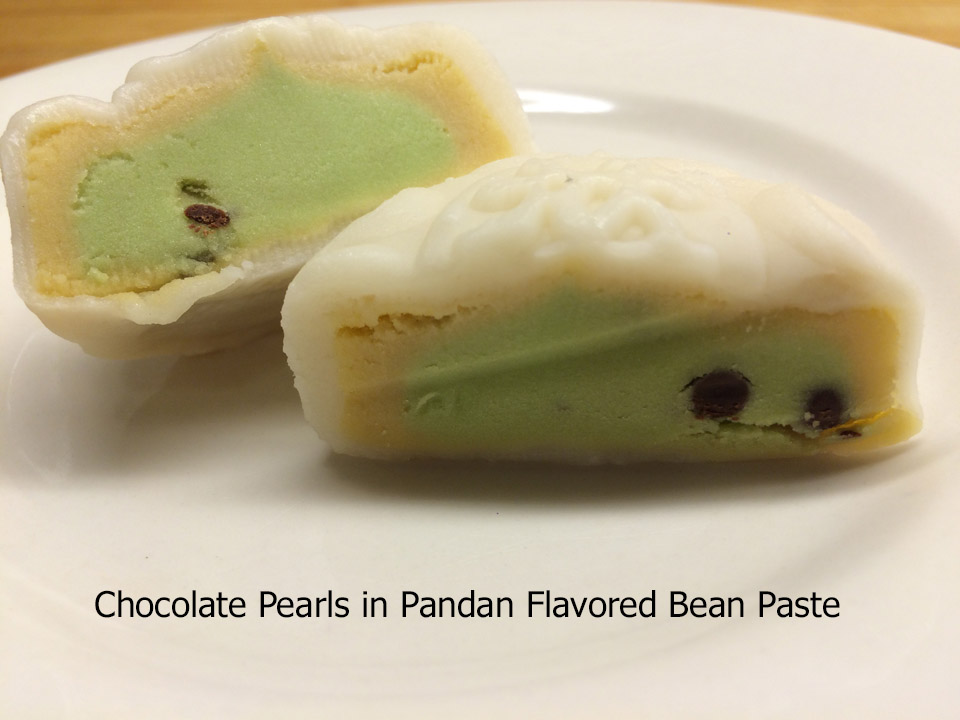

Then there are trendy snow skin versions that hail from Hong Kong all of which are equally accessible and delicious. Think mooncake meets mochi: rather than dough-based and baked, the skins are almost like the sweet Japanese glutinous rice cake, but not quite as chewy. These snowy and icy mooncakes must be kept chilled. The snowy flavors are contemporary: strawberry, mango, orange, pineapple, honeydew, peach, peanut, taro, chestnut, green tea and red bean; one version featured durian flavored sweet bean paste with bits of the fruit and enveloped by a skin of sweet, almost almond paste texture and flavor. Icy mooncakes come two to a box (they’re smaller, about 2 inches by ¾ inch) with imaginative flavors like pandan bean paste with chocolate pearls (tiny crispy, candy bits, crunchy like malted milk balls, but probably puffed rice), dark chocolate bean paste (the skin is like mochi with chocolatey paste on the inside and a piece of dark chocolate or a bit of cream cheese nestled within), durian, mango, blueberry, custard, chestnut, black sesame, strawberry, and cherry. Prices range from $6–$9.50 each or for a box.

It seems that each year brings a fashionable new interpretation, eye-catching and tongue-pleasing, and 2019 was no exception. These sweet multihued gems came from Fay Da Bakery, a chain boasting a baker’s dozen locations (some outside of Chinatown). Our fascination with desserts that gush when pierced is serviced by Lava Mooncakes clad in colorful skins. Purple on the outside, golden within, the durian flavor was perfect; the green matcha member of team proved sweet; yellow custard was eggy – almost duck eggy – and in terms of flavor, a fair hybrid of classic mooncake and this modern rendition; orange was less about lava and more about marmalade, riddled with bits of orange peel – a pleasant surprise.

The Snowskin Mung Bean Mooncakes were also a treat: mango featured a good balance between mung bean and mango; strawberry tasted like strawberry preserves from a jar, not that it was bad, just how it was; purple yam was sweeter than I anticipated and quite flavorsome; durian, like its lava mate, was not overpowering but decidedly durian.

Even the Häagen-Dazs in Flushing’s New World Mall was touting sets of ice cream mooncakes!

Perhaps the most unusual are the mooncakes found in Fujianese neighborhoods, particularly along East Broadway in Manhattan’s Chinatown. These round behemoths (about 8½ inches in diameter or larger and an inch or so thick) are simple in appearance. Wrapped in a single flaky layer covering a more substantial crust (a mixture of rice and wheat flours) with red food coloring stamps on top to delineate varieties, they are an embarrassment of lard and sugar with the addition of chopped peanuts, dried red dates (jujubes), bits of candied winter melon and other nuts and fruits supported by sesame seed encrusted bottoms. I’m wary about cautioning you that these might be an acquired taste as they are certainly unlike anything you might find in Western cuisine and I don’t want to put you off; some friends liked them immediately, others had to think about it. In any event, the flavors will grow on you regardless of your starting point. These hefty disks exemplify the phrase “a little goes a long way” and a cup of tea nearby helps cut the oiliness. Cost is about $10 each.

Perhaps the most unusual are the mooncakes found in Fujianese neighborhoods, particularly along East Broadway in Manhattan’s Chinatown. These round behemoths (about 8½ inches in diameter or larger and an inch or so thick) are simple in appearance. Wrapped in a single flaky layer covering a more substantial crust (a mixture of rice and wheat flours) with red food coloring stamps on top to delineate varieties, they are an embarrassment of lard and sugar with the addition of chopped peanuts, dried red dates (jujubes), bits of candied winter melon and other nuts and fruits supported by sesame seed encrusted bottoms. I’m wary about cautioning you that these might be an acquired taste as they are certainly unlike anything you might find in Western cuisine and I don’t want to put you off; some friends liked them immediately, others had to think about it. In any event, the flavors will grow on you regardless of your starting point. These hefty disks exemplify the phrase “a little goes a long way” and a cup of tea nearby helps cut the oiliness. Cost is about $10 each.

I have to admit that I hit a wall in my attempt to decipher the inscriptions on the Fujianese mooncakes. Most bore a number of red sunburst shaped identifiers and were stamped, once, twice, three times or four. I was hard pressed to taste the difference between the single and double stamped versions; they were the simplest of the lot – sweet, lardy, and a little fruity perhaps. By the same token, the three-stamp and four-stamp versions were similar to each other and boasted the addition of sweet jujubes and other fruits – more interesting and better in my opinion, certainly sweeter because of the jujubes, but I couldn’t tease out the distinction between the two. Alas, there were other stamps as well – words, I suspect – but the color had run so they were undifferentiable to me. I have friends who can handle Mandarin and Cantonese, but not the Fujianese dialect, and none of the vendors had a word of English, so my questions were fruitless (unlike the 4-stamp mooncake). I’m not going to let this go, though, so keep an eye out for an update to this post.

Update as promised: Never one to be satisfied with “…and the rest” (as the theme from television’s Gilligan’s Island once crooned – but only for the first season), I had no choice but to return to East Broadway in Manhattan’s Chinatown where I had first tapped into the motherlode of Fujianese mooncakes.

On that visit, I had spotted one that displayed somewhat illegible writing rather than a mini-constellation of stamps but I had already purchased a surfeit of mooncakes that day and decided that I didn’t really need to buy one of each. Silly me; I should know better by now. So since that particular mooncake was eating at me (instead of the other way around), I hazarded $12 to try and solve the mystery.

This time the writing on the mystery mooncake was clear, but I’m still unsure about what it said. I see the character for “plus” over the one for “work”; if they were next to each other, it would mean “processing” (in addition to lots of other translations). In any event, it’s one of the best of that ilk that I’ve tried because of the ample addition of black sesame seeds and a plentitude of peanuts, so if you encounter it, that’s the one to get.

And here’s an example from 2022: a chunk taken from each of two different Fujianese mooncakes – both very good, but radically different. More research to come, I guess!

I’ve cobbled together a mini-glossary to help you decipher a few characters on some of the more popular fillings found in Cantonese mooncakes:

月 moon

月餅 mooncake

白 white

蓮蓉 lotus seed paste

紅豆 red bean

旦黃 single yolk

雙黃 double yolk

冰 ice

冰皮 snowy

伍 five

仁 nut, seed, kernel, (benevolence)

金華火腿 Jinhua ham

棗 jujube (red date)

Armed with these keys, you can combine phrases and discover the secrets hiding within. For example:

雙黃白蓮蓉 = double yolk white lotus seed

冰皮月餅 = snowy mooncake

So head to your nearest Chinese bakery and sample some of these autumn delights! If you can pronounce pinyin, say “zhōngqiū kuàilè” (which sounds like jong chew kwai luh). But in any language, here’s wishing you a Happy Mid-Autumn Festival!

中秋节快乐!