Or, The Equal Opportunity Celebrant – Part 3

A long time ago in a land far, far away, before I had identified my obsession with world food, when I was merely a youthful gourmand content to consume tasty fare but still light years away from my current soaring orbit of ethnojunkie mania, an acquaintance from what I now know as Little India visited me.

She proffered a small white cardboard box.

Opening my souvenir, I was ambushed by a tempting, heady aroma that I’ll never forget – my first contact with mithai, Indian sweets. Peering within, I discerned a dozen or so colorful tidbits – yellow, orange, pink, green, cream, white, brown, some glistening with what appeared to be thin foil made of silver (and which I later learned actually was thin foil made of silver) and all in distinctive shapes from spheres, disks and cylinders to cubes and diamonds and even a pretzel configuration.

Selecting one, I took a bite. “Not bad,” I allowed, as I made my way from the living room into the kitchen to refrigerate the rest.

Curiously, about twenty minutes later, I found myself woolgathering about these new delicacies so I headed back to dispatch the one I had started earlier. “These are actually pretty good,” I thought as I polished off a second and began nibbling at a third. “Better save some for later,” I reasoned as I stowed the box back inside the fridge.

This time, only about ten minutes passed before I returned to my treasure; in retrospect I suppose I had been reflecting all the while about which one I’d sample next. Standing before the fridge, I devoured a fourth. “Pretty good? No, these are amazing!” I realized in the throes of a sugar-induced epiphany. Replacing the box with my right hand and holding a fifth goody with my left, I elbowed the door closed and attempted to leave the kitchen, but before I could escape, I was compelled to make a U-turn as if by some unseen, powerful force. Yanking the refrigerator door open, I grabbed the container and scurried to the living room. Anxiously, I attempted to rationalize my monomaniacal behavior: I hastily began scribbling detailed notes describing the flavors and textures I was experiencing with each sweet mithai – nuts like almonds, cashews, and pistachios, spices like saffron and cardamom, fruits like raisins and coconut, even carrot; some were redolent of rich dairy, some were thick and fudgy, some soft and syrupy sweet, some creamy, some crispy, some crumbly. But to me, every one was a tiny, delicious miracle unlike anything I had tasted before.

And the monkey on my back emphatically concurred.

That was it. I knew I had to get to Little India – and soon! – so that I could score another parcel and share these delights with my friends. Feverishly, I began making plans: it was imperative that I turn everybody I knew on to mithai. (And obviously, while I was at it, I could land more for myself!)

Perhaps it was this very incident that put the junkie in ethnojunkie.

And now, freely admitting that I am powerless over their sway, I must share my experience with you. This is a particularly good time to do it, since Diwali, the Hindu Festival of Lights, is upon us. From Wikipedia: “One of the most popular festivals of Hinduism, it spiritually signifies the victory of light over darkness, good over evil, knowledge over ignorance, and hope over despair. Its celebration includes millions of lights shining on housetops, outside doors and windows, around temples and other buildings in the communities and countries where it is observed.” In addition to lighting diyas, diminutive and often ornate oil lamps, one of the many rituals is the sharing of mithai, and although I can’t bring each of you to my favorite sweets dealers, I can tell you about some of the diverse types you’re likely to find and what to expect when you taste them.

Varieties of mithai (मिठाई) are regional, from the north, east, south, and west of India, not to mention Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. Many are pan-South Asian as well, but in New York, you’re not likely to see any distinctions other than Indian (most of the shops around Lexington Avenue near East 28th Street in Manhattan and those along 74th Street and 37th Avenue in Jackson Heights, Queens) plus a smattering of Bangladeshi spots (along 73rd Avenue in Jackson Heights). New Jersey also boasts a number of venues in Newark, Edison, and Paterson. My personal favorite as of this writing (and note that things can change in this regard) is Maharaja Sweets at 73-10 37th Avenue in Jackson Heights.

So in general, what do they taste like? You had to ask. I recall reading a story many years ago about how sweetmakers, obsessively dedicated to their craft, are revered in India and how they guard their secrets more closely than they would the Hope Diamond if given the chance, so for any particular type of mithai, recipes will vary widely from one purveyor to the next. The less involved ones might taste like nut-suffused, aromatic dairy fudge or like cheesecake taken to the next level or perhaps like a syrupy, fragrant cake – all with an overarching Indian luster. But there are so many versions of even these, not to mention the more elaborate multi-ingredient confections, that they defy verbal description. To paraphrase Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, you’ll know it when you taste it.

If you took note of the ingredients, textures, and shapes enumerated above and if you’re a math jock, you’ll see that the permutations and combinations within even that short list seem endless. What mithai have in common is that they range from very sweet to outrageously sweet and are all the size of a couple of bites. In this post, I’ll introduce you primarily to hand-held treats and reserve other sweets such as frozen desserts (like kulfi, Indian ice cream), puddings (like kheer, firni, mishti doi, and shrikhand), and drinks (like lassi) for another post.

First, a little vocabulary of ingredients that I promise will come in handy and is sure to obviate numerous pairs of parentheses; English spellings will vary slightly:

badam – almond

kaju – cashew

pista – pistachio

malai – cream

kesar – saffron

gajjar – carrot

besan – chickpea flour, also known as gram flour, often roasted

Types of dairy products used in making mithai:

Ghee – clarified butter.

Chhena – A fresh (unaged) cheese like paneer (you’ve probably had paneer in Indian restaurants) but softer because some whey remains in the finished product.

Khoa, also known as khoya, mawa, and mava. Khoa is amazing: start with a cowful of milk and cook it down until you’re left with a few ounces of milk solids. If you don’t have a cow (and I suggest you don’t), you can buy it prepackaged at Indian markets if you’re considering making your own mithai, which, by the way, is not impossible.

Here are some of the most common types of mithai that you’ll typically encounter, but an exhaustive list would be, well, exhausting. (Click any photo to view in glorious high resolution.)

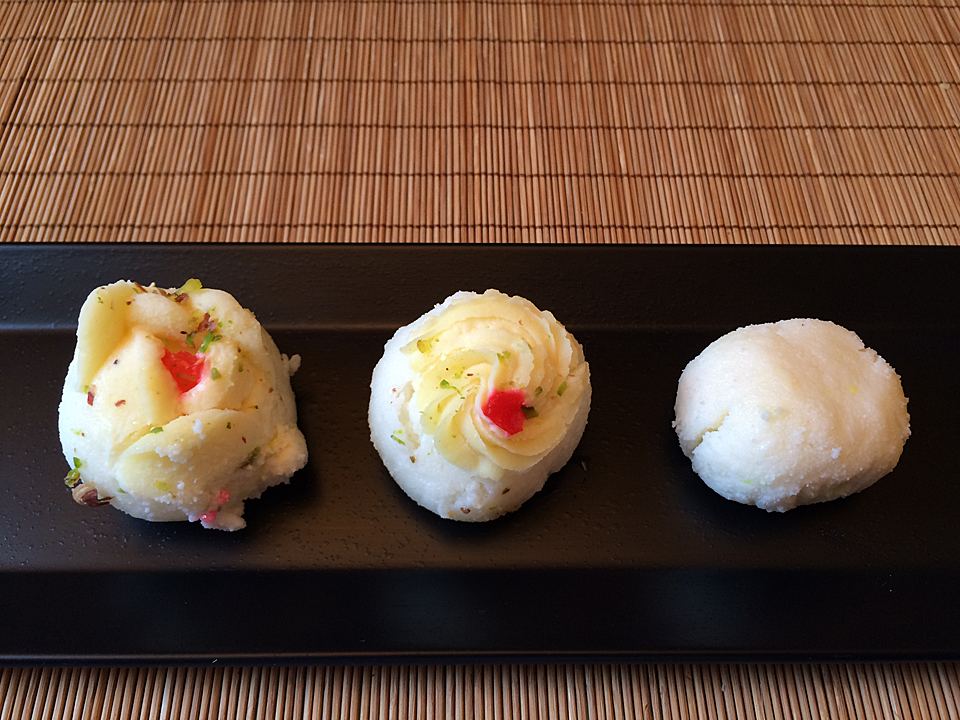

Shown here, kesar badam burfi (these are homemade by the way, so you see it is possible!), peda, and sandesh.

- Burfi (you also might see it as barfi, burfee, etc.) – condensed milk-based with a fudge-like consistency; usually cut into rectangular blocks. Easy to find in many varieties like badam burfi (usually almond colored), kaju burfi (usually a little darker, caramel colored), pista burfi (usually green), malai (usually white), besan, etc. Most feature cardamom, some highlight saffron. The name comes for the word for snow.

- Katli – like burfi but thin, flat, and often cut into diamond shapes. A little denser than burfi. Katli means slice.

- Peda (you also might see it as pera, pedha and penda, the Gujarati spelling) – similar to burfi but enhanced with khoa. Usually found in a disk shape with a pattern imprinted atop.

- Sandesh – similar to burfi but chhena-based and moist with a more open, tender texture.

- Kalakand – deliciously cheesy and chhena-based; more dense than sandesh.

Halwa takes many forms depending upon the region of India from which it hails. From left to right:

- Gajjar (you also might see it as gajar) halwa can be found cut into squares like burfi and also scooped loose from a large container. (Those shown above are also homemade if you’re keeping score.)

- Karachi halwa are translucent and not unlike a very thick, super chewy gumdrop; they’re made from semolina or cornstarch. Often wrapped in plastic to thwart their stickiness.

- Habshi halwa (I’ve also seen something that appears to be the same item called dhoda burfi) are dark brown squares made from besan, nuts, nutmeg and mace. It’s a dead ringer for a chocolate brownie but do not confuse it with its doppelganger: Never think “Oh, yum, chocolate brownie!” when you’re about to tuck into one or your brain and tastebuds will get stupifyingly disoriented. It is absolutely delicious and one of my favorites along with burfi and peda.

Other halwas are made from wheat flour or mung bean flour. The flavors and textures really depend on the versions you come across, so I won’t attempt to provide a universal description, but they generally lie somewhere along the cake/fudge/pudding continuum.

Incidentally, many Indian sweetmakers are using chocolate these days with mixed results in my opinion: in most cases, it just doesn’t work (a terroir thing perhaps?) but every once in a while I’ve hit upon an excellent one and I’ve had to revise my thinking for the moment.

Laddoo and kala jamun. The yellow is shahi (royal) laddoo, the orange is kesar laddoo.

- Laddoo – the word means ball and really only refers to the shape since there are many kinds with many textures and flavors. Flour based and cooked with syrup (some are deep fried as well), a common type is made up of tiny pearl sized balls (boondi) rolled together into a larger sphere. All of them are sugary sweet. These are traditionally offered to the elephant-headed god Ganesha, the remover of obstacles. I have it on good authority that Ganesha loves food!

- Gulab jamun – medium brown in color and universally found not only in sweet shops but also for dessert in Indian restaurants. Deep fried batter (made with khoa but you might not notice it), sphere shaped, and a little spongy so they soak up the sweet rose water syrup they’re swimming in. (Gulab means rosewater, jamun refers to the java plum, a fruit of similar size to gulab jamun.) Kala jamun are similar to gulab jamun, slightly darker in color and sometimes shaped more like cham cham.

- Rasgulla – also found for dessert in Indian restaurants. These white, cheesy confections are made from chhena and semolina, cooked and often served in a sugar syrup, first cousin to gulab jamun.

- Ras malai – spongy and also chhena based, these swim in a creamy sauce; first cousin to rasgulla. Ras means juice.

I think of these next three as related:

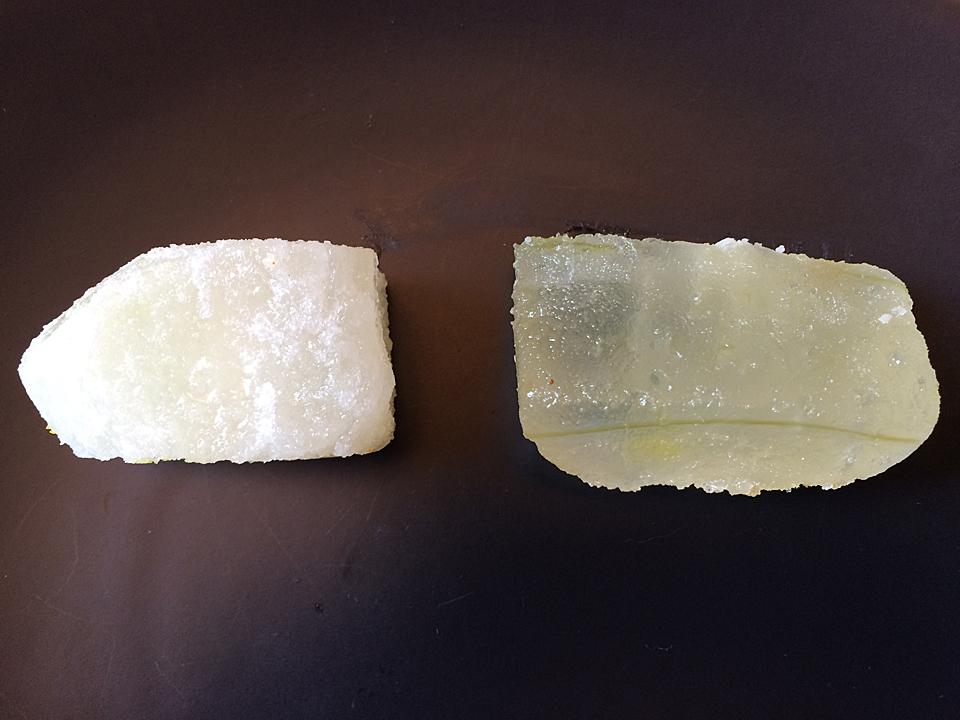

Besan in its many forms figures into so many mithai that I can’t keep track. On the left, smooth and creamy besan burfi and crispy patisa halwa. The photo on the right is a close-up of the layers of almost crystalline flaky striations that create patisa’s delightful crunch.

- Patisa halwa – a chickpea based sweet. Sometimes shaped like little haystacks, sometimes in a block, they are crispy and delicious.

- Mysore pak – made from chickpea flour and ghee, cut into rectangular shapes – if you like chickpeas, you’ll like these. They appear to be spongy, but they’re crumbly and a little crisp.

Dry petha and regular petha, amriti, and pinni.

- Petha – not to be confused with peda or pera, these are a translucent candy made from winter melon/white pumpkin, tasting like perfumed, juicy, sweet candied fruit. You also might see the dry version that is less syrupy, crisper, crunchier, and more candy-like.

- Jalebi – chickpea or wheat flour batter, usually orange but occasionally yellow, is drizzled into hot oil in coil shapes. The resulting deep fried confections look like pretzels; they’re crispy when they come out of the oil, then soaked in syrup so you get the best of both worlds.

- Amriti (you also might see it as imarti) are similar to jalebi, always orange but shaped like a squiggly flower; thicker than jalebi, less crisp, and less sweet.

- Pinni (you also might see it as pinny) – made from wheat flour, koya, jaggery (unprocessed brown sugar), dry fruits and nuts. Less sweet than most, and a welcome change of pace in that regard.

Cham cham in their native habitat (alongside other goodies).

- Cham cham (you also might see it as chum chum or even cham-2) – a little larger than thumb-sized and oblong, often coated in coconut. Typically you’ll see it in white, yellow, and pink although I don’t think the colors are any indication of flavor. Not overwhelmingly dairy, but they are made from milk solids. Although not swimming in syrup (see gulab jamun), these have a slightly spongy texture and hold a little sweet syrup: think juicy but not saturated.

Some mithai like these are scooped out in bulk from bins rather than sold in compact individual pieces; some take the shape of small tidbits.

Some mithai like these are scooped out in bulk from bins rather than sold in compact individual pieces; some take the shape of small tidbits.

Mithai from Bangladesh and Pakistan share some similarities with their Indian counterparts but are crafted from a slightly different set of ingredients and, to my taste, are a little less sweet. I recommend becoming familiar with Indian mithai before essaying these. The photo on the left shows a few treats from Premium Sweets, the Bangladeshi restaurant on 73rd Street in Jackson Heights. On the right is a sampling of the panoply of Pakistani confections I discovered on a recent New Jersey expedition to celebrate Pakistani Independence Day (h/t Dave Cook and his illustrious blog, Eating In Translation) that came from Chowpatty on Oak Tree Road in Iselin; most were pretty good but perhaps a little less accessible than their Indian analogues.

On the Pakistani plate:

Row 1

(1) Badam Puri – flour, rice flour, ground almonds, milk, sugar, cardamom; fried in oil, a delicious wafer.

(2) Watermelon/Anarkali – not watermelon flavored that I could discern but similar in appearance; edible silver foil, green on the outside, red on the inside.

(3) Halwasan Pak – cracked wheat, edible gum (looks like little pebbles), ground “porridge”, milk, almonds, cashews, brown sugar, nutmeg, cardamom; very crunchy, almost sandy.

Row 2

(1) Gundar – dry fruit, gum arabic crystals, powdered ginger; strongly flavored, an acquired taste.

(2) Gajar Halwa – see above.

(3) Kaju Mohini – figs and nuts, tastes like it looks.

Row 3

(1) Adadiya Pak – urad dal (lentils), gram flour, nuts, ginger, fenugreek and other spices, roasted in ghee; texture like crunching on sandy pebbles, an acquired taste.

(2) Stuffed Peda – see above.

(3) Gundar Pak – syrupy gundar.

Row 4

(1) Ghari – the white “icing” had very little flavor, almost tasted like wax or oil; green pista inside.

(2) Dryfruit Halwa – made with raisins, truly delicious.

(3) Halwasan – made from cracked or broken wheat and soured milk; chewy, fruity.

And finally, more photos to get you hooked. As you might expect, special mithai are created for Diwali. One that is particularly delicious, unique and one of my all-time favorites is apple mithai (the two peach-colored pieces in the first photo), complete with a clove for a stem; this seasonal sweet tastes a lot like marzipan and has a very limited run through Diwali only; it’s a specialty of Rajbhog Sweets, 72-27 37th Avenue in Jackson Heights. The rest are always available.

So that’s my addicted-to-mithai story and I’m sticking to it (and possibly to the Karachi halwa as well). I urge you to go out there and track down these confections, especially for the holiday although most are available year-round. If they don’t light your diya, I don’t know what will. And if, after you’ve sampled them, an insatiable craving for mithai sneaks up on you when you least expect it…well, you know how you got hooked!

दिवाली मुबारक

Happy Diwali!

In 2019, Diwali begins on Sunday, October 27.

Excellent!! A beautiful presentation of exotic treats. Good info on the main ingredients, the different choices, and the sources. Very well done — Thanks!!

2fat