Instagram Post 3/4/2020

#mithailove #mithais #tellastory

(One of my “Favorites” that never fails to resonate this time of year. If you enjoy reading it, there are more in the column on the right side of my home page.)

Gong Xi Fa Cai! The callithump of Chinese drums and cymbals played havoc with my ears as the pungent miasma of spent fireworks assaulted my nose. “These are my people!” I beamed. An equal opportunity celebrant, I was in my element.

Gong Xi Fa Cai! The callithump of Chinese drums and cymbals played havoc with my ears as the pungent miasma of spent fireworks assaulted my nose. “These are my people!” I beamed. An equal opportunity celebrant, I was in my element.

I picked my way through the ankle-deep sea of technicolor metallic streamers and confetti. “Looks like a dragon exploded,” I mused. Shuffling from market to crowded market, each festooned with the accoutrements of the holiday, I searched for authentic goodies with which to welcome the Chinese observance of the Lunar New Year in style.

Definition: Chinese New Year, also known as Spring Festival, is a dazzling two-week long celebration occurring in January or February, a banquet for the soul that is laden with more symbolism than a Jungian interpretation of a Fellini dream sequence inspired by a Carlos Castaneda novel.

The shape of the holiday’s foods suggests their analogue: dumplings are crafted to resemble Chinese gold or silver ingots, long noodles emblematize a long life, melon seeds epitomize fertility. Color plays a significant role as well: mandarin oranges allude to the color of gold. Sweets are often tinted red, the color of good fortune in Chinese culture.

But nothing is more traditional to the Chinese New Year banquet than food-word homophones. As any precocious third grader will tell you, homophones are words that sound alike but have different meanings (for, four, and fore in English, for example). At these festive gatherings, a whole fish will be served, because the word for fish (yu) is a homophone for surpluses. Also gracing the table will be Buddha’s Delight, a complex vegetarian dish that contains an ingredient the name of which sounds like the word for prosperity.

(We don’t have that kind of thing in western culture, but maybe we should. Imagine if you rang in the New Year at an American restaurant by ordering the surf ‘n’ turf, a certain portent that this would be the year that you meat your sole mate.

Just don’t wash it down with wine.)

And no traditional food is more important than the ubiquitous Chinese New Year delicacy, nian gao, a glutinous rice cake sweetened with brown or white sugar and a homophone for “high year” — with the connotation of elevating oneself higher with each new year, perhaps even lifting one’s spirits.

Now, I had seen nian gao dished up and steamed in aluminum pie pans in every market in New York’s five or so Chinatowns. But one particular variation packaged in a six-inch wide container shaped like a Chinese ingot (as many items are this time of year) caught my eye and beckoned to me. As I inspected it more closely, I realized that I could not for the life of me fathom how it open it! This fact alone was sufficient bait; I stood in line with my fellow revelers, paid, and took it home.

With bugged-out eyes and a glower that betrayed both puzzlement and frustration, I turned the semi-translucent vessel over and over again like someone who had reached a cul-de-sac with a recalcitrant Rubik’s Cube. The object was fashioned of two mirror image concave pieces of plastic fused together — plastic somewhat thicker than that of the average shampoo container — too thick to squeeze easily, for sure, and inseparable along the seam. I could make out an air bubble which migrated as I shifted its orientation, so I had a clue as to the texture of its contents — typical semi-firm glutinous rice cake, perhaps with a little syrup around it. Searching for an instruction manual, I found that Google had abandoned me: either no one else on the planet had ever encountered these contrivances or everyone else on the planet buys them every year and I am the only soul who is too inept to persuade them to yield their bounty. There was a tissue paper-thin label stuck to the bottom that showed the “best before” date as May, so even allowing for my customary procrastination, I had some time to solve the mystery. As long as that case remained closed, the case was not closed.

Wait a minute. What if some sort of key was hiding beneath that slip of a label? A slot to pry the two halves apart or a helpful arrow embossed on the obdurate plastic? Slowly, carefully, I began to peel back the label. THHHHPPP! The tiny air bubble instantly expanded to fill half the case as air rushed inside. Could it be that this gossamer leaf was the only protection the rice cake had from the elements, furry predators, and me? Such was the fact.

But then, I was confronted with a further conundrum. Lurking beneath said label was a hole the size of a half dollar. (Remember those?) This carapace was obviously a mold constructed so that its contents would delight the eye when served. But the only way I could see to get to the goods inside was to dig the stuff out with a fork! Not what they intended, I was certain. Somehow, there had to be a way to pry the halves apart without damaging the springy contents.

I hooked my thumbs on either side of the hole and yanked. Gnrrgh! Nothing. I laid it on the kitchen counter and pressed down with as much muscle as I could muster hoping that it would split along some weak, unseen fault line without damaging the contents. Again, it did not succumb to my efforts. I grabbed my nastiest knife and attempted to slice through the case along the seam. Nope, that’s not it either, I thought as I licked my finger where I had cut myself when the blade slipped.

Silently, the ingot mocked me. Was it designed this way on purpose? Some sort of arcane object lesson about anything worth achieving is worth struggling over? Or conversely, was it perhaps trying to tell me that I would never achieve riches, no matter how much I persevered?

Frustrated, I stashed the thing in a corner of my fridge. Days passed. The days melded into weeks. It was time to begin plans for Thanksagaingiving.

Definition: Thanksagaingiving is a joyful, annual family ritual. Not content to celebrate the merely dozens of diverse international and American holidays, each with its own panoply of tempting traditional foods, I created one more.

Over many years, I have developed, tweaked, and perfected an elaborate Thanksgiving menu that I prepare annually, much to the delight of my clan. And over those many years, we would ask ourselves, why don’t we do this more often? Pondering the possibility, we recognized that just about every month has some delectable holiday or seasonal foods associated with it. But there is that frigid, desolate chasm between Chinese New Year and the promise of tender spring vegetables that cries out for a joyous — and delicious — festival to uplift us from our disheartened doldrums.

Enter Thanksagaingiving. When we give thanks. Again. And rerun the whole November spectacle.

Invariably, each day as I loaded the fridge with more ingredients for our feast, it became necessary to move the Chinese ingot around to make space for the latest bounty. Now onto the second shelf, the customary residence for leftovers, now far back into the lower left corner where that jar of homemade boysenberry jam had been languishing for the last three months, now precariously balanced on a tall bottle of pandan syrup lying on its side in the least accessible corner — where the ingot unfailingly teetered, slipped, and fell, locking its neighbors into an exasperating jigsaw of jars and urns that prevented anything from being extricated from the shelf.

I had no choice but to toss it.

Our annual Thanksagaingiving tradition came and went. We happily devoured our Roast Turkey with Chestnut Cornbread Stuffing, Dandy Brandied Candied Yams, Maple Sugar Acorn Squash, Corn Pudding, Scalloped Potatoes with Leeks and Bacon, and the subsequent procession of turkey sandwiches, turkey tetrazzini, turkey burritos, and turkey soup.

The fridge was once again barren. Wistfully, I gazed at the empty spaces that my forlorn little nian gao had been sequentially evicted from. Had I forsaken it prematurely? Would one more hour of negotiation have solved the mystery? Nostalgically, I remembered all the time we had spent together getting to know each other.

But then, I realized that all was not lost — come next Chinese New Year, I could purchase another ingot-encased nian gao and try again. I felt my spirits lifting.

And suddenly, I comprehended what had come to pass without my even being aware of it. In the light of that existential moment, the words “come next Chinese New Year, I could purchase another…and try again” echoed in my mind — and the cosmic meaning of this episode, the raison d’être for this tortuous journey became brilliantly clear:

It had been the maiden voyage of a new annual tradition!

(And speaking of maiden voyages, please join me on one of my ethnojunkets, food-focused walking tours through New York City’s many ethnic enclaves. Learn more here.)

(Click on any image to view it in high resolution.)

恭禧發財! Gōng xi fā cái!

The Chinese celebration of the Lunar New Year is upon us!

4718 is the Year of the Rat 🐀. I’m no Chinese zodiac scholar, but based on what I see in our subway system, rats are extremely talented when it comes to accessing food and are happy to indulge in a comprehensive variety of cuisines, never playing favorites.

I can relate to this.

And apropos of eating, there’s one aspect of this spectacular holiday that I particularly enjoy and that’s the way wordplay and homophones factor into the selection of traditional foods. An example is nian gao, a glutinous rice cake sweetened with brown or white sugar and a homophone for “high year” – with the connotation of elevating oneself higher with each new year, perhaps even lifting one’s spirits.

But there was one year when my inner rat was thwarted in attempting to access a particular nian gao – and what should have literally been a snap turned into a complete mystery.

Curious? Please read my very short story, “The Case of the Uncrackable Case!”

Originally posted on September 6, 2019. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, some businesses may be closed – temporarily, we hope – and prices may vary. The Mid-Autumn Festival, however, will be with us forever – as long as there are autumns to celebrate!

(Click on any image to view it in high resolution.)

A visit to any Chinatown bakery this time of year will reveal a befuddling assemblage of mooncakes (yue bing) in a seemingly infinite variety of shapes, sizes, colors, ornamentation, and fillings, all begging to be enjoyed in observance of the Mid-Autumn Festival. Also known as the Autumn Moon Festival, this important holiday occurs on the fifteenth day of the eighth lunar month (around mid-September or early October on the Gregorian calendar) when the moon looms large and bright – the perfect time to celebrate summer’s bounteous harvest. They’re sold either individually or in attractive gift boxes or tins since it’s customary to offer gifts of mooncakes to friends and family (or lovers!) for the holiday. Since my porcine appetite apparently knows no bounds (2019 is the year of the pig – how appropriate 😉), I felt compelled to purchase an assortment of these delicacies in order to learn about their similarities and differences and to shed some light (moonlight, of course) on their intricacies.

The first point to note is that various regions of China have their own distinct versions of mooncakes. A quick survey of the interwebs revealed styles hailing from Beijing, Suzhou, Guangdong (Canton), Chaoshan, Ningbo, Yunnan, and Hong Kong, not to mention Taiwan and Malaysia. They’re distinguished by the types of dough, appearance, and fillings, some sweet and some more savory. In my experience, Chinese bakeries in Manhattan, Brooklyn (Sunset Park), and Queens (Flushing) favor the Cantonese style, but Fujianese mooncakes are easy to find along stoop line stands outside of markets in neighborhoods where there’s a concentration of folks from Fujian.

You’ll commonly find mooncakes with doughy crusts (golden brown, soft, somewhere between cakey and piecrusty, often with an egg wash sheen) as well as those with white, paper thin flaky layers that betray lard as a critical ingredient; chewy glutinous rice skins (these aren’t baked); and gelatinous casings (jelly, agar, or konjak), the most difficult to find in the city. Golden-baked, elegantly decorated Cantonese versions are round (moon shaped, get it?) or square, are fluted around the perimeter, and have been created using molds made of intricately carved wood to provide the ornate design or an inscription describing what’s inside (see photo).

Fillings among the Cantonese types are dense and sweet and include lotus seed paste, white lotus seed paste, red bean paste, and mung bean paste, sometimes with one or two salted duck egg yolks (representing the harvest moon) snuggled within. In addition, there are five-nut (or -kernel or -seed) versions, packed with chopped peanuts, walnuts, almonds, pumpkin seeds, and watermelon seeds as well as a variety made with Jinhua ham, dried winter melon, and other fruits buried among the nuts; its flavor was a little herby, not unlike rosemary, but I couldn’t quite identify it. These last two were particularly tasty. All are about 3 inches wide and 1½ inches high and sell for about $4.50–$6; mini-versions are available as well.

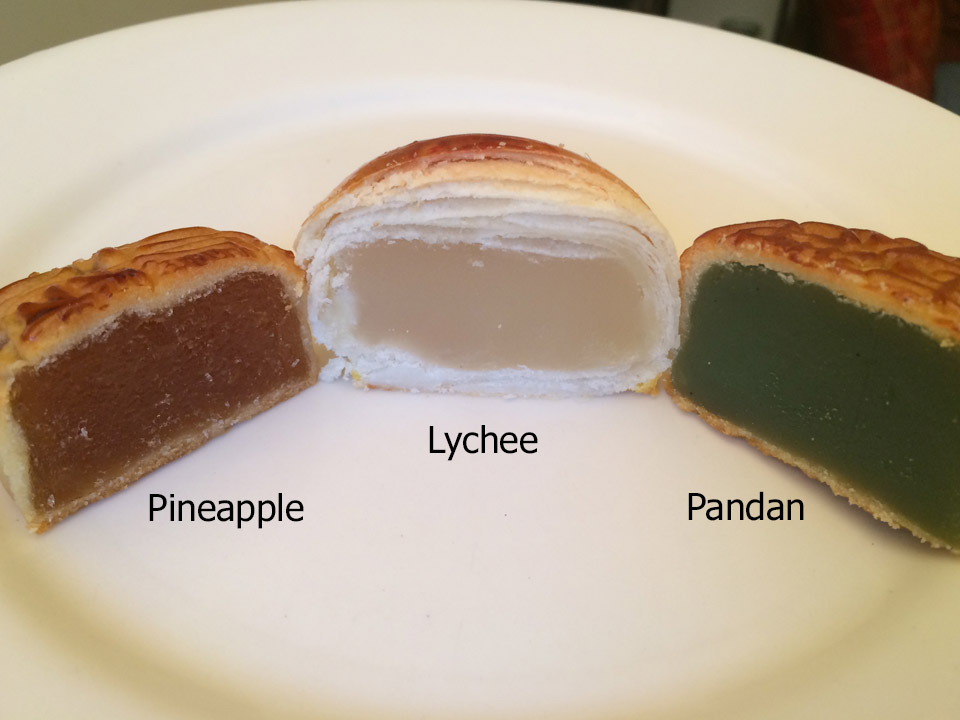

A visit to Flushing exhibited all of these as well as some outstanding fruity varieties including pineapple, lychee, and pandan; these can be best described as translucent fruit pastes and are perfect for the novitiate – a gateway mooncake if ever there was one.

Here are two pandan mooncakes, one with preserved egg yolk and a mini version without, from Fay Da Bakery at 83 Mott Street in Manhattan’s Chinatown.

Here are two pandan mooncakes, one with preserved egg yolk and a mini version without, from Fay Da Bakery at 83 Mott Street in Manhattan’s Chinatown.

In another market, I found a white, flaky pastry version, Shanghai style, I believe; the filling was like a very dense cake with a modicum of nuts and fruits providing some contrast and crunch – certainly tasty.

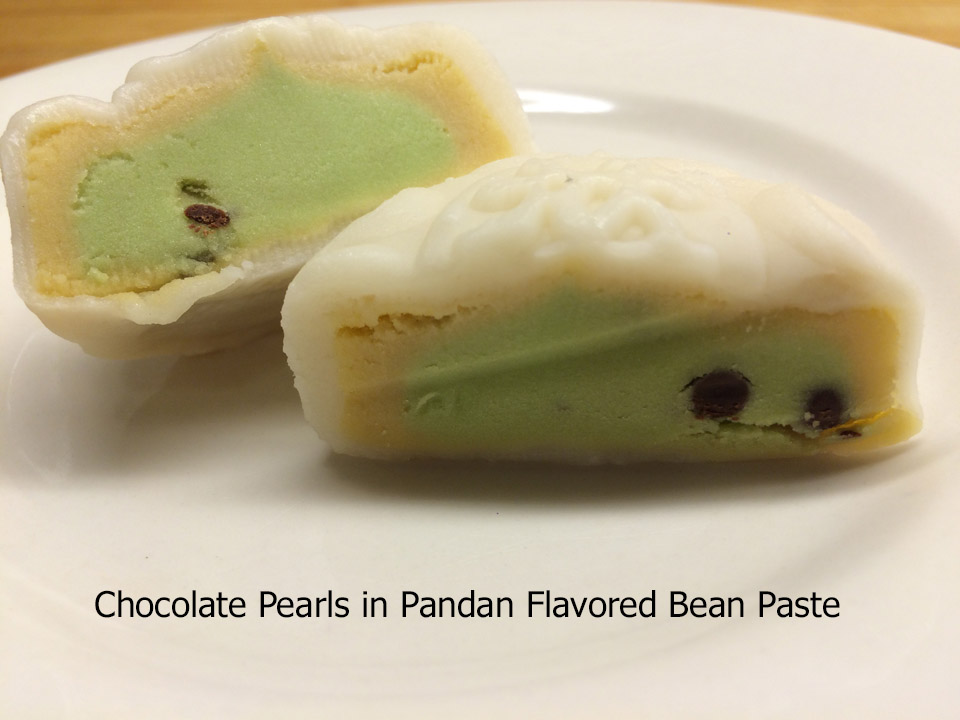

Then there are trendy snow skin versions that hail from Hong Kong all of which are equally accessible and delicious. Think mooncake meets mochi: rather than dough-based and baked, the skins are almost like the sweet Japanese glutinous rice cake, but not quite as chewy. These snowy and icy mooncakes must be kept chilled. The snowy flavors are contemporary: strawberry, mango, orange, pineapple, honeydew, peach, peanut, taro, chestnut, green tea and red bean; one version featured durian flavored sweet bean paste with bits of the fruit and enveloped by a skin of sweet, almost almond paste texture and flavor. Icy mooncakes come two to a box (they’re smaller, about 2 inches by ¾ inch) with imaginative flavors like pandan bean paste with chocolate pearls (tiny crispy, candy bits, crunchy like malted milk balls, but probably puffed rice), dark chocolate bean paste (the skin is like mochi with chocolatey paste on the inside and a piece of dark chocolate or a bit of cream cheese nestled within), durian, mango, blueberry, custard, chestnut, black sesame, strawberry, and cherry. Prices range from $6–$9.50 each or for a box.

It seems that each year brings a fashionable new interpretation, eye-catching and tongue-pleasing, and 2019 is no exception. These sweet multihued gems came from Fay Da Bakery, a chain boasting a baker’s dozen locations (some outside of Chinatown). Our fascination with desserts that gush when pierced is serviced by Lava Mooncakes clad in colorful skins. Purple on the outside, golden within, the durian flavor was perfect; the green matcha member of team proved sweet; yellow custard was eggy – almost duck eggy – and in terms of flavor, a fair hybrid of classic mooncake and this modern rendition; orange was less about lava and more about marmalade, riddled with bits of orange peel – a pleasant surprise.

The Snowskin Mung Bean Mooncakes were also a treat: mango featured a good balance between mung bean and mango; strawberry tasted like strawberry preserves from a jar, not that it was bad, just how it was; purple yam was sweeter than I anticipated and quite flavorsome; durian, like its lava mate, was not overpowering but decidedly durian.

Even the Häagen-Dazs in Flushing’s New World Mall was touting sets of ice cream mooncakes!

Perhaps the most unusual are the mooncakes found in Fujianese neighborhoods, particularly along East Broadway in Manhattan’s Chinatown. These round behemoths (about 8½ inches in diameter and an inch or so thick) are simple in appearance. Wrapped in a single flaky layer covering a more substantial crust (a mixture of rice and wheat flours) with red food coloring stamps on top to delineate varieties, they are an embarrassment of lard and sugar with the addition of chopped peanuts, dried red dates (jujubes), bits of candied winter melon and other nuts and fruits supported by sesame seed encrusted bottoms. I’m wary about cautioning you that these might be an acquired taste as they are certainly unlike anything you might find in Western cuisine and I don’t want to put you off; some friends liked them immediately, others had to think about it. In any event, the flavors will grow on you regardless of your starting point. These hefty disks exemplify the phrase “a little goes a long way” and a cup of tea nearby helps cut the oiliness. Cost is about $10 each.

Perhaps the most unusual are the mooncakes found in Fujianese neighborhoods, particularly along East Broadway in Manhattan’s Chinatown. These round behemoths (about 8½ inches in diameter and an inch or so thick) are simple in appearance. Wrapped in a single flaky layer covering a more substantial crust (a mixture of rice and wheat flours) with red food coloring stamps on top to delineate varieties, they are an embarrassment of lard and sugar with the addition of chopped peanuts, dried red dates (jujubes), bits of candied winter melon and other nuts and fruits supported by sesame seed encrusted bottoms. I’m wary about cautioning you that these might be an acquired taste as they are certainly unlike anything you might find in Western cuisine and I don’t want to put you off; some friends liked them immediately, others had to think about it. In any event, the flavors will grow on you regardless of your starting point. These hefty disks exemplify the phrase “a little goes a long way” and a cup of tea nearby helps cut the oiliness. Cost is about $10 each.

I have to admit that I hit a wall in my attempt to decipher the inscriptions on the Fujianese mooncakes. Most bore a number of red sunburst shaped identifiers and were stamped, once, twice, three times or four. I was hard pressed to taste the difference between the single and double stamped versions; they were the simplest of the lot – sweet, lardy, and a little fruity perhaps. By the same token, the three-stamp and four-stamp versions were similar to each other and boasted the addition of sweet jujubes and other fruits – more interesting and better in my opinion, certainly sweeter because of the jujubes, but I couldn’t tease out the distinction between the two. Alas, there were other stamps as well – words, I suspect – but the color had run so they were undifferentiable to me. I have friends who can handle Mandarin and Cantonese, but not the Fujianese dialect, and none of the vendors had a word of English, so my questions were fruitless (unlike the 4-stamp mooncake). I’m not going to let this go, though, so keep an eye out for an update to this post.

Update as promised: Never one to be satisfied with “…and the rest” (as the theme from television’s Gilligan’s Island once crooned – but only for the first season), I had no choice but to return to East Broadway in Manhattan’s Chinatown where I had first tapped into the motherlode of Fujianese mooncakes.

On that visit, I had spotted one that displayed somewhat illegible writing rather than a mini-constellation of stamps but I had already purchased a surfeit of mooncakes that day and decided that I didn’t really need to buy one of each. Silly me; I should know better by now. So since that particular mooncake was eating at me (instead of the other way around), I hazarded $12 to try and solve the mystery.

This time the writing on the mystery mooncake was clear, but I’m still unsure about what it said. I see the character for “plus” over the one for “work”; if they were next to each other, it would mean “processing” (in addition to lots of other translations). In any event, it’s by far the best of any of that ilk that I’ve tried because of the ample addition of black sesame seeds and a plentitude of peanuts, so if you encounter it, that’s the one to get.

I’ve cobbled together a mini-glossary to help you decipher a few characters on some of the more popular fillings found in Cantonese mooncakes:

月 moon

月餅 mooncake

白 white

蓮蓉 lotus seed paste

紅豆 red bean

旦黃 single yolk

雙黃 double yolk

冰 ice

冰皮 snowy

伍 five

仁 nut, seed, kernel, (benevolence)

金華火腿 Jinhua ham

棗 jujube (red date)

Armed with these keys, you can combine phrases and discover the secrets hiding within. For example:

雙黃白蓮蓉 = double yolk white lotus seed

冰皮月餅 = snowy mooncake

So head to your nearest Chinese bakery and sample some of these autumn delights! If you can pronounce pinyin, say “zhōngqiū kuàilè” (which sounds like jong chew kwai luh). But in any language, here’s wishing you a Happy Mid-Autumn Festival!

中秋节快乐!

(Click on any image to view it in high resolution.)

The Chinese celebration of the Lunar New Year is upon us!

One aspect of the holiday that I particularly enjoy is how wordplay and homophones factor into the selection of traditional foods. An example is nian gao, a glutinous rice cake sweetened with brown or white sugar and a homophone for “high year” – with the connotation of elevating oneself higher with each new year, perhaps even lifting one’s spirits.

This is the Year of the Pig 🐷 which, of course, is my cue to taste every traditional delight I can get my trotters on, but there was one year when the means by which to sample a particular nian gao turned into a complete mystery.

Curious? Please read my very short story, “The Case of the Uncrackable Case!”

(Click on any image to view it in high resolution.)

I wrote a story about Durian Pizza in Flushing for Edible Queens. It begins:

There’s an old adage about durian: “Smells like hell, tastes like heaven!”

Whatever you may have heard about this fruit, it probably wasn’t encouraging. Some regard durian with mild amusement, some with outright disdain, while others have come to appreciate its unique personality. My objective is to disabuse you of any prejudices you may harbor about the “King of Fruits” (as it’s known in Southeast Asia) and direct you to a local restaurant where you can indulge—fearlessly—in its charms….

It’s the most wonderful time of the year! That time when folks dust off words like ’tis and ’twas as Bing Crosby croons creaky, arthritic chestnuts with inscrutable lyrics like “Christmas is a-comin’ and the egg is in the nog….”

That one always baffled me. I mean, what else would be in the “nog”?

There is vigorous unresolved debate over the etymology of the word “eggnog” (or phrase “egg nog”, if you prefer), proof that anything so resplendent is worthy of detailed analysis and ultimately obsession. Investigation harkens back to the late 1600s and hypotheses range from the term for a strong ale or possibly the wooden mug it was served in to a scrambled portmanteau of colonial argot, “grog” (rum) and “noggin” (mug). Eggs and dairy never even entered the picture (or perhaps, in this case, the pitcher). A libation did exist, however, called “posset” that was prepared with alcohol, milk, spices, and sometimes eggs, quaffed by the Brits during medieval times, that persisted for centuries. The recipe underwent refinement (as all worthy recipes do) and was surely the forerunner of today’s glorious elixir.

Inevitably, there are those who refuse to be satisfied until they’ve added a little something extra to the standard issue brew: down south, eggnog is often spiked with bourbon, not to mention Southern Comfort, but sherry, brandy, cognac, whiskey, rum, and grain alcohol, individually or in combination, have all managed to stagger into America’s punch bowl. Of course, this wouldn’t be an ethnojunkie post without at least a nod to international mixology, so from Wikipedia: “Eggnog is called coquito in Puerto Rico, where rum and fresh coconut juice or coconut milk are used in its preparation. Mexican eggnog, also known as rompope, was developed in Santa Clara. It differs from regular eggnog in its use of Mexican cinnamon and rum or grain alcohol. In Peru, eggnog is called biblia con pisco, and it is made with a Peruvian pomace brandy called pisco. German eggnog, called biersuppe, is made with beer and eierpunsch is a German version of eggnog made with white wine, eggs, sugar, cloves, tea, lemon or lime juice and cinnamon.” The list goes on. (Speaking of far away places with strange sounding names for things, I have to admit a certain fondness for the French spin on the word for eggnog, lait de poule – hen’s milk.)

All of which raises the question of whether I favor mixing eggnog with alcohol. I was afraid you’d ask. My personal observation is that it’s a waste of good booze and a waste of good eggnog. Unless of course it’s homemade (the nog, not the hooch) but that’s a nag of a different color. This post is about commercial eggnogs, and we’re only considering dairy based entries at that – not soy, rice, coconut, or almond milk nor lactose-free rivals – simply because there would undoubtedly be winners and losers among those categories which would eventually be pitted against “the real deal” and that would only serve to complicate comparisons.

If you’ve read me, you know that I have a few (ha!) guilty pleasures when it comes to holiday food, and for me, nothing heralds the advent of the season like the first appearance of eggnog on supermarket shelves. And snatching it away precipitately as they do every year when the yule log’s embers have barely begun to evanesce only makes the anticipation and craving for next year’s batch more intense.

But which one(s) to buy? Fret not. I and my OCD are here to offer you the benefits of my research and experimentation regarding this happy holiday quandary.

You probably know that flavor variations among brands of eggnog aren’t like those of milk – milk tastes pretty much like milk regardless of the purveyor (there are nuances but they’re not worth considering in this context). The dissimilarities among brands of eggnog, however, are cosmic by comparison; they may as well be different beverages. And to complicate things, a few brands taste radically different from year to year. (My theory is that there is some sort of practice among smaller dairies where they acquire the flavor base from a third party source and blend it with their own milk, but sometimes, for whatever reason, the base changes – perhaps it’s sourced from an alternate supplier, perhaps it’s a mandated change in recipe – hence the extreme annual variance within a single brand. It’s all about that base.) Note also that some brands are local and unique while others are the regional offspring of a national food company that may provide the same product under varying names (see the Garelick and Tuscan cartons above, both brought to you by Dean Foods).

Having read dozens of reviews, I find it fascinating that there is absolutely no critical agreement as to which commercial eggnog tastes best; one reviewer’s nectar of the gods is another’s paint thinner, so it is evident that eggnog’s charms are very much in the mouth of the beholder. My own memories of the bewitching flavor of the Ethereal Eggnog of My Youth remain vivid to this day and are the genesis of the impassioned quest I am about to share with you. But even if you disagree with my personal preferences, you’ll be able to make use of the template I’ve devised in order to develop the ultimate eggnog of your sugarplum dreams.

The strategy is to identify significant universal eggnog characteristics and rate how each contender performs in each category. Picture a table, the kind that folks use Excel spreadsheets for even though there are no numbers to crunch but that are ideal for sorting data. Headers across the first row are Brand, Vintage, Body, Creaminess, Artificial/Natural, Flavor Notes, Finish, Special Features, Comments, and Overall Rating. Let’s examine each:

• Brand – seems obvious, but might include subtitles like Hood’s brood of Golden, Caramel, Cinnamon, Sugar Cookie, Pumpkin Pie, and Vanilla flavors; the single column simplifies sorting.

• Vintage – the year you’re evaluating. This is useful for two reasons: Tracking by year can identify certain brands that vary annually. For example, in 2008 (yeah, I’ve been at this for a while), Farmland was running well but then for a few years it had drifted to the middle of the pack; happily, in 2018 it hit its stride again. It’s like waiting for this year’s vintage Beaujolais Nouveau to appear: Le 2018 Farmland Lait de Poule est arrivé! And some unpredictability can be welcome; after all, it wouldn’t be Christmas without some surprises. Farmland actually comes in handy, as you’ll see later.

The second reason is that some brands never change and that’s a good thing because it can make life easier. For example, in 2014, I sampled (and had unsurprisingly forgotten about) International Delight and observed that the flavor notes included Butter Rum Lifesavers (not in my nog, thank you very much). Then in 2017, I inadvertently bought it again and my butter rum flavor notes were identical to those from three years earlier. Since my comments ran along the lines of “worst ever”, “the word ‘egg’ never even appears on the label nor in the ingredients list so no surprise there”, and so forth, it’s obvious that I’ll never need to carry that brand home again. See? Makes life easier.

• Body – rated on a 1 to 5 scale where 1 is thinnest and 5 is thickest. You might not care for a super thick eggnog (or the yellow mustache that accompanies it), so maybe a 4 in this category beats a 5 for you, but it certainly shouldn’t be a 1, otherwise you’re just drinking eggnog flavored milk and what’s the point of that? But it’s all a matter of taste, as is everything in this post.

• Creaminess – different from body, this is about mouthfeel where 1 may very well be thick but not at all creamy (think Pepto-Bismol) and 5 coats your mouth with dairy cream.

• The Artificial/Natural continuum – where 1 denotes dominant artificial flavoring (usually ester-based) and 5 tastes like someone made it at home using only eggs, dairy products and sugar. Appreciation of this trait is idiosyncratic. Personally, I’m trying to recapture the Magical Eggnog of My Kidhood and that one had just a wee dram of that ester component. To understand them, you first need to know that there are many flavors derived from ester compounds. You’ll find them in artificial flavors of every stripe but probably the most universally recognized example I can describe is that artificial banana-y flavor of Circus Peanuts, those orange, oversized-peanut-shaped, marshmallowy candies that are an affront to the tastebuds of anyone over the age of five. That’s only one kind of ester (isoamyl acetate, C7H14O2, for my fellow science geeks out there) but there’s a common combination that screams “Eggnog!” to anyone whose tongue is half listening. I’m searching for just a soupçon of that in my nog.

• Flavor Notes – for example, descriptors like eggy, nutmeggy, vanilla, cinnamon, clove, carrageenan (a thickener often found in commercial rice puddings and a flavor easy to recognize once you’ve experienced it), cooked, nutty, or sugary sweet.

• Finish – you oenophiles will grok this. A food’s aftertaste is often different from its flavor (think artichokes) and it’s connected to whatever remains on your tongue plus the sense memory that you’re left with after taking a sip. I once had some eggnog that was sort of okay in the mouth but whose aftertaste was downright chalky. I’ve found that a few organic brands have a “grassy” finish.

• Special Features – categories like organic, lite (whatever that means), and if you must, soy/nut/coconut-based, lactose free, etc. This is the column in which I noted that SoCo actually provides instructions on its label, admitting, “Preparation: Mix with Southern Comfort” so perhaps it’s intended to work optimally in that application – as a mixer, not a beverage – since I don’t care for it as a virgin standalone. Again, that’s just me; YMMV.

• Comments – have fun with it. One eggnog I tasted (which will go nameless) inspired me to write, “tastes the way my parents’ plastic slipcovers used to smell when I was a kid.”

• Overall Rating – where 1 is worst and 5 is best. Do not confuse this with an average of any numerical ratings you may have assigned. Think of it as how many stars out of five you’d give the product.

Now as you buy particular brands of eggnog (I’ve been through dozens of brands and vintages), fill in the cells in the table. I recommend using a blind taste test form listing the aforementioned categories so that you’re not haunted by ghosts from Christmas past in the row above competing for your attention, but you don’t have to. (I did warn you that this was an OCD undertaking, right?)

So you’ve collected a mountain of data but how do you use it? Surely there is no such thing as the perfect commercial eggnog as the lack of consensus among reviewers would suggest. I find those beverages always lacking in one dimension or another and that’s where this chart comes into play. The best way I can demonstrate its application is to show you how I’ve implemented the information to recreate the taste of my Childhood Enchanted Eggnog.

In 2017, Ronnybrook Farm Dairy’s eggnog was pretty darned delicious straight out of the (deposit) bottle (I gave it a 4.5 overall) and if you wanted to just buy one brand without all this folderol (or falalalalalderol perhaps) it would have topped the list, but its carrageenan and guar gum levels make it a little thicker (rated 5 for body) than the Nog of My Dreams. That’s where a solid middle of the road eggnog like that year’s Farmland (3.5 overall) comes into play. Farmland is a journeyman level nog, modest and nicely balanced in terms of flavor, and coming in at 3.5 on the body scale is the perfect addition to mitigate Ronnybrook’s viscosity while not overpowering its essence. But when I cut Ronnybrook with it, an ineffable characteristic was missing. Another sip. Ah, the ester component, of course – which was ultimately provided by Turkey Hill. Turkey Hill scored a 1 on my artificial/natural scale (way too estery for me) but a dollop of it added to the Ronnybrook/Farmland mix was all the recipe needed. Three parts Ronnybrook to two parts Farmland plus a good glug of Turkey Hill was the ratio I formulated. (Don’t forget to garnish with a bit of freshly grated nutmeg!)

Another time, when I couldn’t locate Farmland for my attenuation purposes, I was able to procure Cream-O-Land (whose slogan used to be “Made From Real Cows” before some marketing guru thought the wiser of it). That year’s batch was okay but nothing special (rated 3 overall), certainly not horrible, but its 2.5 score for body indicated that it could provide the tempering influence that was called for. Since Cream-O-Land is more artificial tasting than Farmland, bringing Turkey Hill into the lineup was unnecessary.

Incidentally, if you’re wondering about 2018’s trials, Ronnybrook has lost a bit of its luster; a 50-50 blend of that and Trader Joe’s was rather good. And oddly, a 50-50 blend of over the top Turkey Hill and under the radar Cream-O-Land was a hit as well.

So there you have it. Yes, I concede that this venture involves imbibing an ocean of eggnog and ignoring a volcano of calories. It’s a tough job, but somebody’s gotta do it.

Needless to say, you shouldn’t feel that you need to slavishly follow my recipe proportions or recommendations. The takeaway here is for you to identify the special characteristics you’re seeking in the eggnog of your fantasies, and piloted by a little R&D as you navigate the nogosphere, come up with your own bespoke, personalized blend.

Incidentally, recounting your saga comes with the delicious bonus of dumbfounding your discriminating foodie friends.

And perhaps your therapist. 😉

Happy Holidays!

Back in the seventies (ahem), Saturday Night Live did a sketch about Scotch Boutique, a store that sold nothing but Scotch Tape. They carried a variety of widths and lengths to be sure, but that was it. Just Scotch Tape.

Back in the seventies (ahem), Saturday Night Live did a sketch about Scotch Boutique, a store that sold nothing but Scotch Tape. They carried a variety of widths and lengths to be sure, but that was it. Just Scotch Tape.

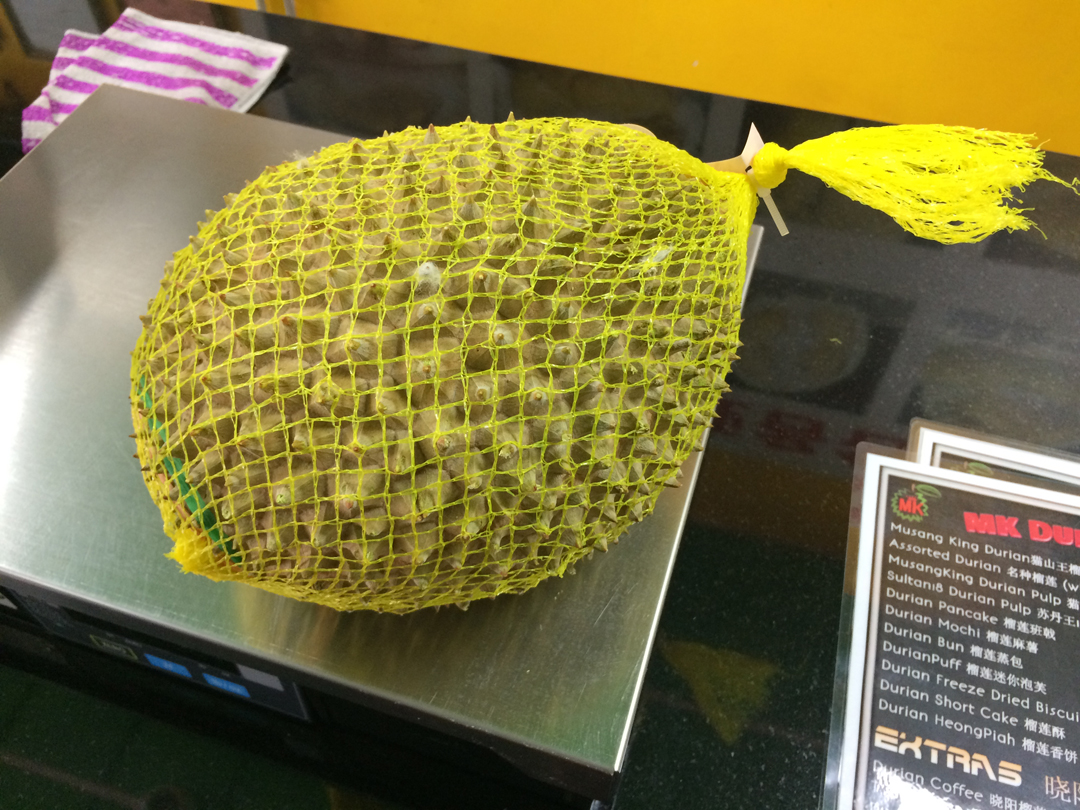

MK Durian Group at 5806 6th Ave in Sunset Park, Brooklyn sells nothing but durian. They carry a variety of cultivars and variations to be sure, but that’s it. Just durian.

And the durian they carry is wonderful.

You’ve probably heard the oft-quoted aphorism about it, “Tastes like heaven, smells like hell” (some would have the order of the phrases swapped but you get the idea), so much so that the fruit is banned from hotels, airlines and mass transit in some parts of the world. (And yes, I’ve been known to smuggle some well-wrapped samples home on the subway.) If you’ve never tasted durian, you might discover that you actually like it; a number of folks I’ve introduced it to on ethnojunkets have experienced that epiphany. There are gateway durian goodies too, like sweet durian pizza (yes, really), durian ice cream, candies, and freeze dried snacks and they’re all acceptable entry points as far as I’m concerned.

It’s difficult to pinpoint what durian smells like. The scent appears to defy description; I’ve encountered dozens of conflicting sardonic similes, but suffice it to say that most people find it downright unpleasant. Although I have a pretty keen sniffer, somehow its powerful essence doesn’t offend me although I am acutely aware of it – just lucky I guess, or perhaps I’m inured to it – because this greatly maligned, sweet, tropical, custardy fruit is truly delicious. So I was thrilled to learn about MK Durian Group (aka MK International Group) from Dave Cook (Eating In Translation) whom I accompanied on a visit there.

Often called the King of Fruits (perhaps because you’d want to think twice about staging an uprising against its thorny mass and pungent aroma), it comes by its reputation honestly but with a footnote. The divine-to-demonic ratio varies depending upon the cultivar and, if I understand correctly, a window of opportunity when certain cultivars are sweet and nearly odorless simultaneously. This, I believe, is durian’s best kept secret. But more about that in a moment. (Click on any photo to view it in high resolution.)

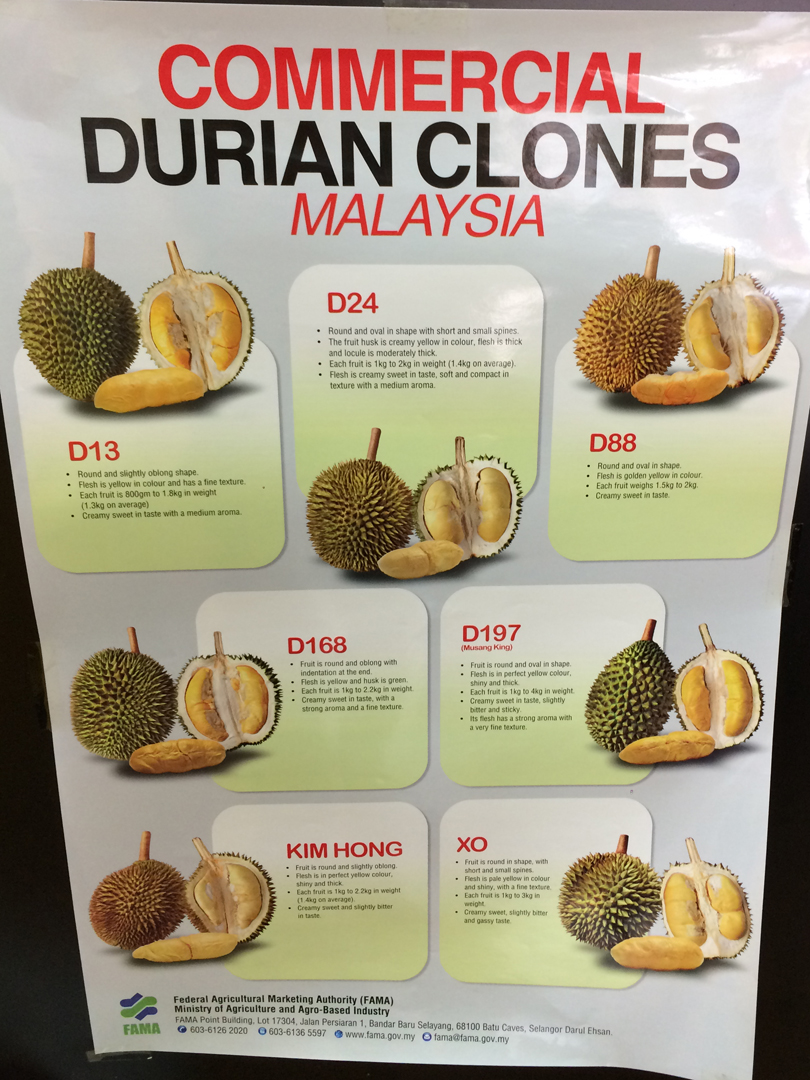

MK Durian Group works directly with plantations in Malaysia and is a wholesaler and distributor to restaurants and retailers in addition to catering to walk-in customers. We entered the commodious space with its many tables, all unoccupied at the time. Chinese-captioned signs showing photos of fifteen cultivars and another seven in English decked the walls along with a menu that, in addition to a price list for the fruit itself, included durian pancakes, mochi, and a variety of cakes, buns, and biscuits, a concession to the timid, perhaps. Durian cultivars are typically known by a common name and a code number starting with the letter “D”, so you might see Sultan (D24) or Musang King (D197), but sometimes you’ll find just the code numbers or sometimes just names like XO or Kim Hong. Scientists continue to work on hybrids to maximize flavor and minimize unpleasant smell.

Fion, without whom I would have been at a complete loss, urged us to get the Musang King, often regarded as the king of the King of Fruits. She selected one from the freezer case and microwaved it for a few minutes to thaw it but not warm it up. Our four pounder, stripped of seeds and rind, ultimately produced about one pound of (expensive but) delicious fruit.

Fion, without whom I would have been at a complete loss, urged us to get the Musang King, often regarded as the king of the King of Fruits. She selected one from the freezer case and microwaved it for a few minutes to thaw it but not warm it up. Our four pounder, stripped of seeds and rind, ultimately produced about one pound of (expensive but) delicious fruit. Using an apparatus that looked a little like some sort of medieval torture device to crack the husk, she then adeptly removed the yellow pods; each pod contains a single seed that can be used in cooking like those of jackfruit. The fact that the receptacle used for holding the durian looked like a crown was not lost on me – truly befitting the King of Fruits. We took our treasure to one of the tables where boxes of plastic poly gloves were as ubiquitous as bottles of ketchup would be on tables at a diner.

Using an apparatus that looked a little like some sort of medieval torture device to crack the husk, she then adeptly removed the yellow pods; each pod contains a single seed that can be used in cooking like those of jackfruit. The fact that the receptacle used for holding the durian looked like a crown was not lost on me – truly befitting the King of Fruits. We took our treasure to one of the tables where boxes of plastic poly gloves were as ubiquitous as bottles of ketchup would be on tables at a diner.

That Musang King was perhaps the best durian I had ever tasted, so much so that my new personal aphorism is “Durian: The fruit that makes its own custard.”

You may have seen durian in Chinatown in yellow plastic mesh bags where the fruit is often sold by the container and you don’t have to buy a whole one; you might conceivably experiment with whatever is available. But these were a cut above. As we left, I realized that something about the experience had been unusual: I asked Dave if he had noticed any of the customary malodourous bouquet. He replied no, but he thought perhaps he was a little congested that morning. I knew I wasn’t congested that morning. There had been no unpleasant smell to contend with. Had we stumbled upon that elusive golden window of odorless but sweet opportunity? Was that particular Musang King odor free? Or perhaps all of them in that lot? Did it have something to do with the fact that it had been frozen and thawed? We were beyond the point of going back and asking Fion, but I think it’s worth a return visit to get some answers!

Daylight Saving Time, my second favorite holiday after Christmas and the undisputed harbinger of Spring as long as you don’t look out your window, has at long last arrived. Two notable celebrations of the season, Easter and Passover, are concurrent this year, so this post is a nod to both. I haven’t forgotten Nowruz, of course, the Iranian (or Persian) New Year that occurs on the vernal equinox, but I feel that it deserves a post of its own accompanied by photos of delicious traditional foods which, with some luck, I’ll be able to provide.

It’s no coincidence that the Italian word for Easter (pasqua) and the Hebrew word for Passover (pesach) are closely related, although culinarily the holidays couldn’t be more disparate. During this time of year, Jewish families are expunging their homes of even the most minuscule crumb of anything leavened, and Italians are baking Easter breads like they’re going out of style.

Italy’s traditional seasonal bread is La Colomba di Pasqua (“The Easter Dove”), and it is essentially Lombardy’s Eastertime answer to Milan’s Christmastime panettone. These deliciously sweet, cakey breads, in some ways Italy’s gift to coffeecake but so much better, are fundamentally the same except for two significant distinctions: the colomba is baked in the shape of the iconic dove that symbolizes both the resurrection and peace, and the recipes diverge with the colomba’s dense topping of almonds and crunchy pearl sugar glaze. Traditionally, a colomba lacks raisins, favoring only candied orange or citron peel, but as with panettone, fanciful flavors (including some with raisins) proliferate. And also as with panettone, charming but somewhat specious tales of its origin abound. (If you haven’t already, please read my passionate paean to panettone for more information and folklore about this extraordinary contribution to the culinary arts.)

(Click any photo to see it in high resolution.)

(Click any photo to see it in high resolution.)

The first photo shows a colomba in all its avian splendor. Frankly, I think it’s a leap of faith to discern a dove in there, but if you can detect one, you may have just performed your own miracle.

Hard pressed to see the dove? Fret not, for the second photo has the cake turned upside down so the columbine form is somewhat more evident.

The third photo depicts a version that features bits of chocolate and dried peaches within and crunchy crushed amaretto cookies atop.

Just wondering: There’s no debate that American kids bite the ears off their chocolate Easter bunnies first. Do you suppose that Italian children start with the head, tail, or wings of the colomba?

On to Passover. Previously on ethnojunkie.com, I did a springtime post that included a story about someone who dared me to come up with an ethnic fusion Passover menu. I wrote:

“Well, far be it from me to dodge a culinary challenge! So although obviously inauthentic, but certainly fun and yummy, here’s to a Sazón Pesach!

Picante Gefilte Pescado

Masa Ball Posole

Brisket Mole

Poblano Potato Kugel

Maple Chipotle Carrot Tzimmes

Guacamole spiked with Horseradish

Charoset with Pepitas and TamarindoAnd, of course, the ever popular Manischewitz Sangria!”

It was all in good fun, of course, but it got me thinking about actually creating a Jewish-Mexican fusion recipe. It isn’t strictly Kosher for Passover, of course, but I thought the concept was worth a try. So here is my latest crack at cross cultural cooking: Masa Brei!

Now you might know that Matzo Brei (literally “fried matzo”) is a truly tasty dish consisting of matzos broken into pieces that are soaked briefly in warm milk (some folks use water), drained, soaked in beaten eggs until soft, then fried in copious quantities of butter. Typically served with sour cream and applesauce, it’s heimische cooking at its finest, Jewish soul food, and it’s easy to do.

So I thought it might be worth a try to swap out the matzos for tostadas, the milk for horchata, the sour cream for crema, and the applesauce for homemade pineapple-jalapeño salsa. A sprinkle of tajín, a scatter of chopped cilantro – and it actually worked! Here’s the finished product:

And no matter which one you’re celebrating (or perhaps all of them like me) – Happy Holidays!

(Click on any image to view it in high resolution.)

It’s no mystery that Chinese New Year is upon us. But I have been baffled by a conundrum that continues to elude me – and despite this year’s zodiac sign 🐕, this mystery has nothing to do with the Hound of the Baskervilles. Read my very short story, “The Case of the Uncrackable Case”!