One of my experiments with homemade Lahpet Thoke, Burmese Tea Leaf Salad

Long ago when I lived in the Village, I was introduced to Burmese cuisine at a restaurant on East 7th Street called Village Mingala. I confess to having eaten my way through their entire menu, annotating items I liked best, and bringing friends as often as I could in order to partake of some delicious, and otherwise difficult to find, dishes. Despite my best efforts to singlehandedly keep them in business, they closed many years ago, so taking the road less travelled as is my wont (read: making things difficult for myself), I decided that I’d better learn to cook Burmese food. You can see some of the fare I prepared for a Myanmar-themed birthday party here. Cloning Ohn No Khao Swè – noodles in a curried chicken and coconut milk broth with besan (chickpea flour that figures notably into the cuisine) – was pretty straightforward, but to this day I can’t even come close to their Thousand Layer Pancake. Couldn’t even get to a hundred. In addition to Village Mingala’s imposing assortment of first-rate noodle dishes, the Burmese salads were always a high point of any meal I enjoyed there. One universal favorite on the menu was Tea Leaf Salad.

In Myanmar, tea is not only drunk, but also consumed as food. Lahpet (you’ll also see it as laphat, laphet, lephet, leppet, letpet, latphat, lat-phat or let-phet as it’s spelled on Village Mingala’s menu – yes, I kept a copy from 2008) is the Burmese word for pickled or fermented tea leaves. It’s pronounced [ləpʰɛʔ] if you’re keen to flex your International Phonetic Alphabet muscles. Thoke means salad (pronounce the “th” like an aspirated “t”). Stick them together, as in lahpet thoke, and you’ve got yourself one addictive dish. (Also note that some folks claim to get a buzz from the caffeine in the tea leaves; I don’t, but YMMV.)

The quest turned out to be a learning experience that stretched across many years. One thing I learned from some Burmese acquaintances craving the flavor of home is that they simply go to the market and buy it ready-made rather than rolling their own. Typically it’s found in a two-part kit comprising the dressed, ready-to-eat tea leaves along with a bag of what I’ll call “crunchies”; those are the two essential ingredients of lahpet thoke. If you’ve never experienced tea leaf salad, understand that it usually isn’t composed exclusively of tea leaves; rather, they’re combined with some raw veggies and are an accent, albeit a significant one, to the ingredient list.

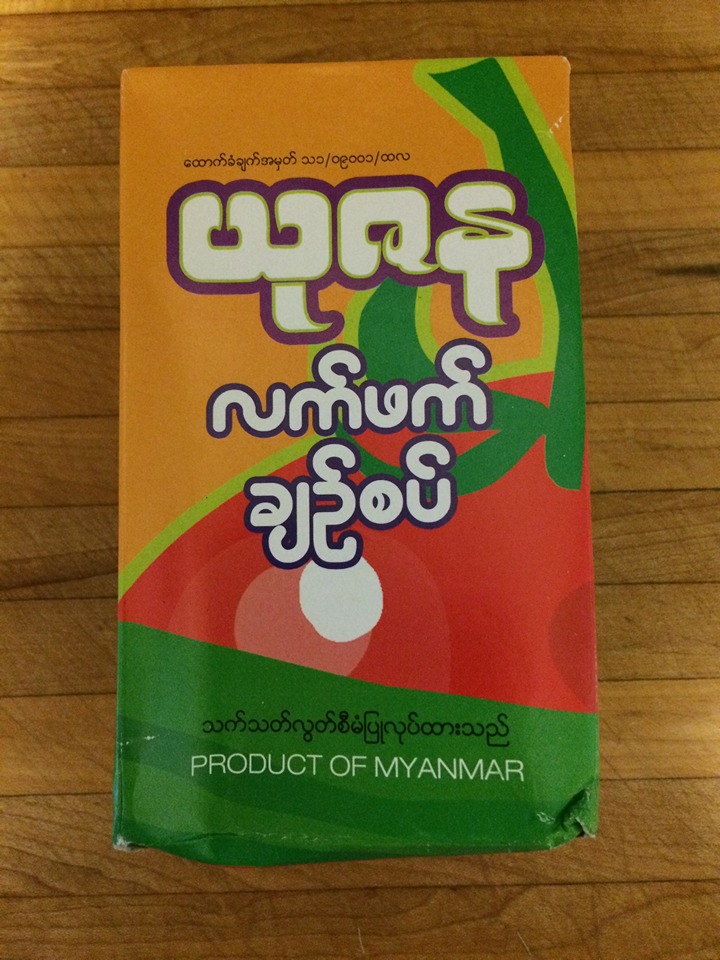

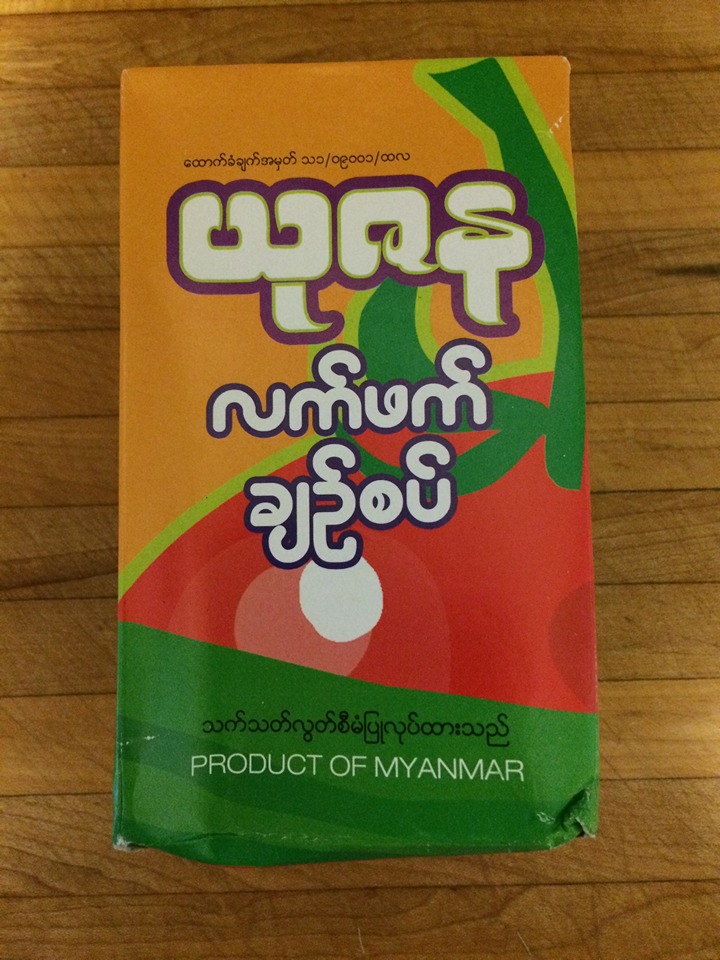

If you want to buy what I refer to as a kit, there’s a teeny room (barely a store) called Little Myanmar Mini Mart (37-50 74th Street in Jackson Heights, Queens) that sells a number of brands of prepared lahpet thoke. It’s easy to miss because it’s so small: go in through the narrow entrance, ignore the phone store on the right, don’t go down the stairs, save Lhasa Fast Food at the far end for later so you can sample their wonderful momos; just turn left and follow the signs (in Burmese IIRC) for the Mini Mart. Don’t give up. They’re there.

Each time I’ve visited, there’s been something new and different on the shelves, and to my mind that makes up for the modest size of the shop, so repeat visits are in order. Here are two of the kits I tried; they were similar but distinctive, and both were tasty.

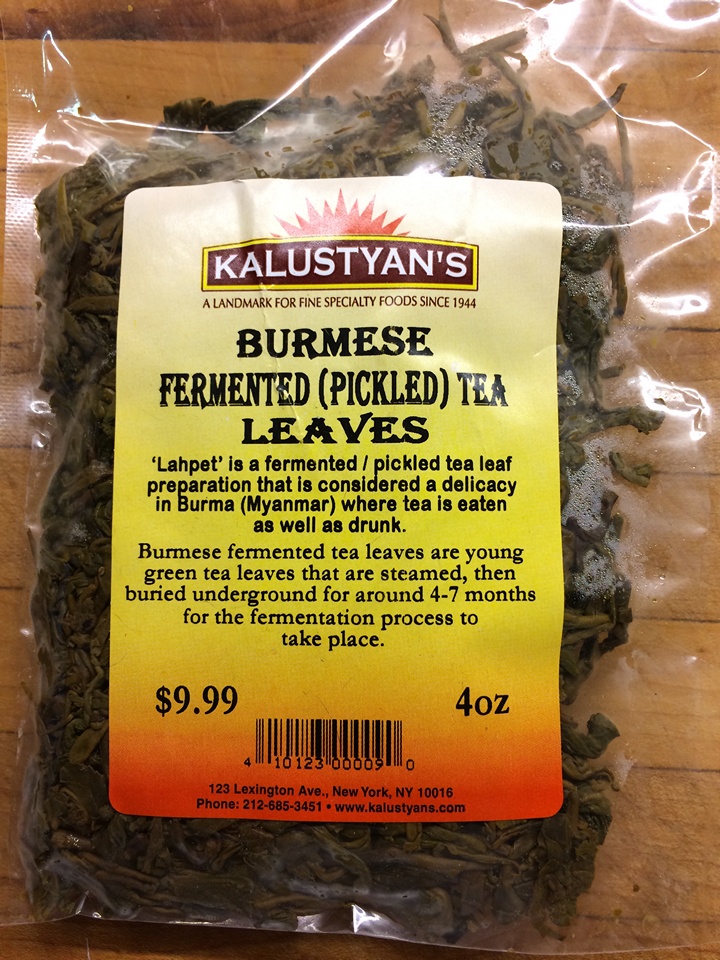

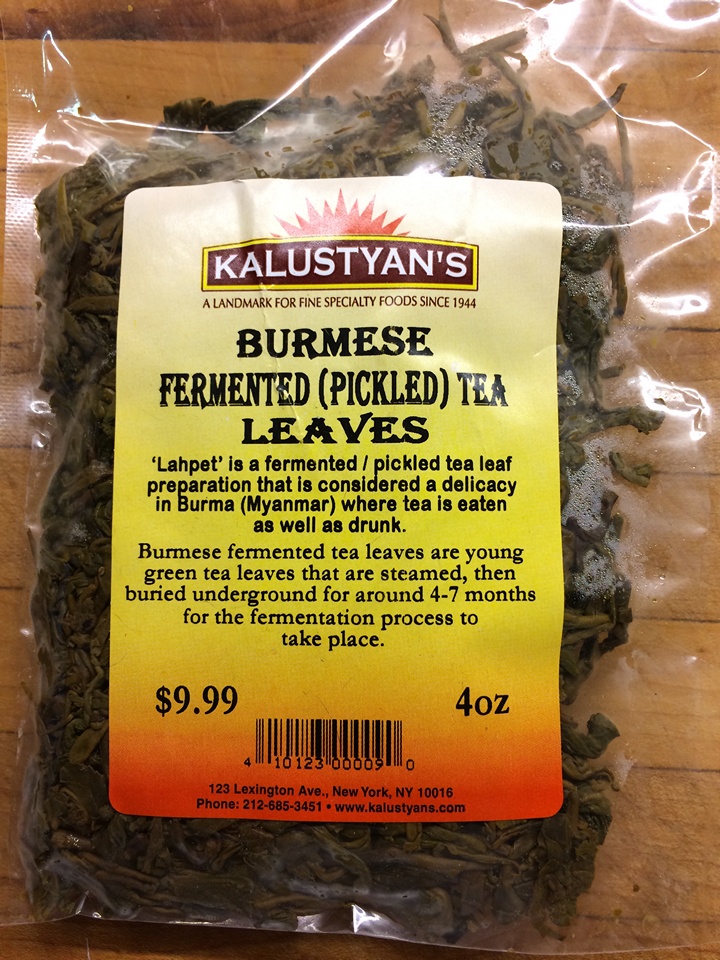

However, I wanted to try making my own dressing for the tea leaves from scratch (the road less traveled, remember?) and I found undressed leaves both at Little Myanmar and also at Kalustyan’s (123 Lexington Avenue near East 28th in Manhattan).

The leaves in this condition aren’t ready to eat. Absent any dressing, they taste a lot like tea (unlike the prepared leaves in the kits), a little bitter, and appear very different as well. In the third photo, the plain leaves are on the right, the other two are the prepared versions from the kits mentioned above. I didn’t detect any fermented or pickled flavor but that’s where the dressing comes into play. You’ll need to soak them in lukewarm water, squishing them a bit with your hands. Drain and squeeze out the water. Repeat, then add cold water and let them stand overnight; the leaves will open up. Then drain, squeeze thoroughly to remove excess water, discard any stems or tough parts, and chop finely.

There’s no unique recipe for the dressing, but between my Burmese cookbooks and the interwebs, here’s what I came up with for an amount sufficient to dress a medium sized handful of leaves. Combine thoroughly:

3 Tbl very garlicky garlic oil

3 Tbl fresh lime juice

1 Tbl fish sauce

½ tsp salt

½ tsp sugar

a little ngapi (a spicy Burmese shrimp paste), to taste

Marinate the tea leaves in the mixture for at least one day in the refrigerator, two if you want them to get down and get funky. If they didn’t taste fermented before, they will now. After they’ve surrendered to the marinade, drain them well, and if you like, chop them a bit more, even as fine as pesto, but I prefer them with a little more definition.

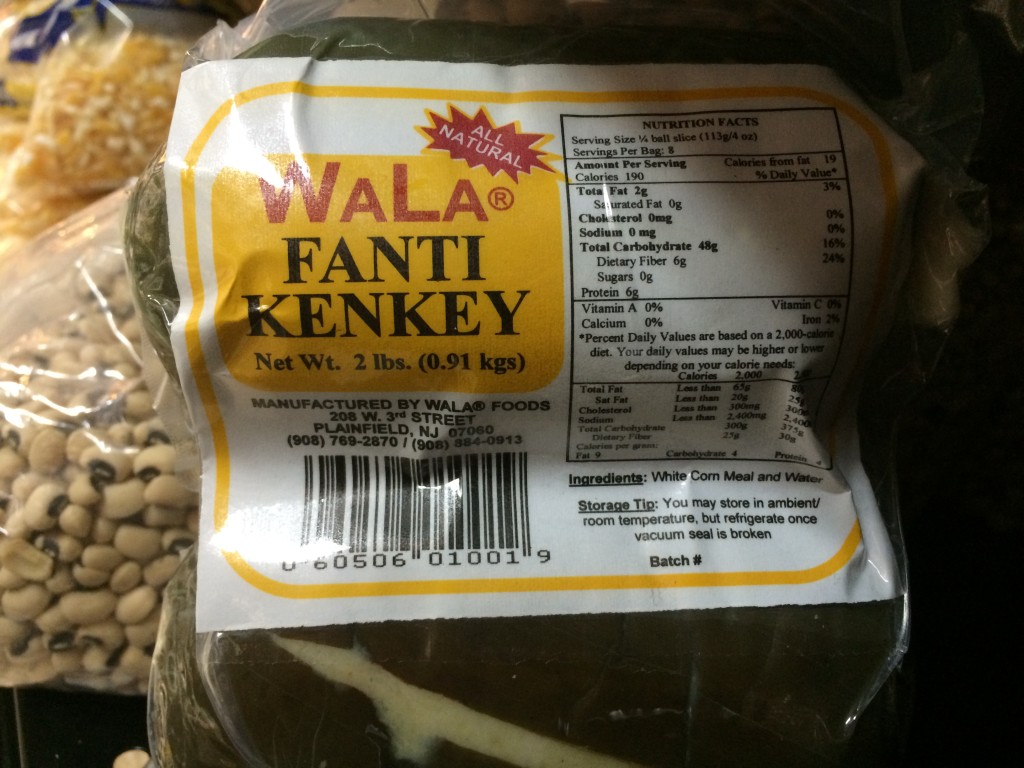

And then ya got yer crunchies. Again, there’s no set ingredient list, but I played around with a mixture of the following:

Fried garlic and fried onion (you can buy those two in plastic jars in any Asian market)

Fried broad beans and toasted soybeans (again, available in bags at any Asian market) plus peanuts and sesame seeds

Briefly fry the legumes and sesame seeds in a little oil (I used peanut oil), just enough to give them some color, enhance the flavor and add a little extra crunch. Drain on paper towels and cool completely. (The sesame seeds brown fastest so add them a little later and be vigilant.) I added this step because the contents of the bags of crunchies in the kits always seem to be a little oily, in a good way. Test for salt, but it will probably be okay.

Finally, the salad component. I used shredded napa cabbage (savoy works too) and halved grape tomatoes. I also soaked some dried shrimp in hot water for a few minutes and added them to the mix. I’ve seen lahpet thoke made with dried anchovies, but I already had enough crunch and salt and wanted a different texture to complement the funkiness element. (Speaking of funkiness, dried shrimp powder also makes a good addition.) Depending upon your tolerance for heat, you can add some chopped green bird’s-eye chilies. Garnish with lime wedges.

In Myanmar’s state of Shan where it’s called Niang Ko, tea leaf salad includes cilantro, scallion and shredded fresh ginger and since I like those in this recipe, I incorporated them as well. Further, in Shan they mix everything together for serving, as I’ve done here; elsewhere, the elements are arranged separately affording the opportunity to personalize the dish to those who’d rather roll their own thoke.

As it were.