(Click on any image to view it in high resolution.)

Looking through my photos for a sweet way to celebrate Pride Month and I found this – from a post about some great food from Dek Sen, the Isaan Thai restaurant in Elmhurst. (Where I just happen to do an ethnojunket! 😉)

Author Archives: Rich

Santacruzan Festival 2022

The 44th Annual Santacruzan Festival and Flores de Mayo celebration in Jersey City last Sunday encompassed two stages for live performances, a flea market, family activities, and religious processions – but you know I was there for the food vendors! Here are a few delicious Filipino treats that we sampled:

(Click on any image to view it in high resolution.)

Lechon (pork belly) – With its all-important crispy skin, served over a split rice ball and accompanied by a cucumber-tomato-onion salad.

Sisig – Plated over rice; pork on one side, chicken on the other.

Longganisa – Filipino sweet sausage that, regardless of its name, is more like chorizo than Spanish longaniza.

Isaw – Grilled pork intestine on a stick with sukang pinakurat (a savory vinegar sauce). The vendor eyed me skeptically. “You eat this?” she asked. “You made this? I eat this!” I replied. Don’t knock it till you’ve tried it.

Masarap!

Flushing Ethnojunkets Are Back!

Snacking in Flushing – The Best of the Best!

I resumed Exploring Eastern European Food in Little Odessa about a month ago and Ethnic Eats in Elmhurst more recently – now Flushing is stepping up to the plate! (And Bay Ridge is just around the corner.)

Ethnojunkets FAQ:

Q: What’s an ethnojunket anyway?

A: An ethnojunket is a food-focused walking tour through one of New York City’s many ethnic enclaves; my mission is to introduce you to some delicious, accessible, international treats that you’ve never tasted but soon will never be able to live without.

Q: Which neighborhoods do you cover?

A: My most popular tours are described on the ethnojunkets page but there are always new ones in the works. For the time being, I’m only scheduling Little Odessa, Elmhurst, and Flushing.

Q: When is your next ethnojunket to [fill in the blank: Flushing, Elmhurst, Little Odessa, Little Levant, etc.]?

A: Any day you’d like to go! Simply send me a note in the “Leave a Reply” section below or write to me directly at rich[at]ethnojunkie[dot]com and tell me when you’d like to experience a food adventure and which ethnojunket you’re interested in – I’ll bet we can find a mutually convenient day! (Pro Tip: Check the weather in advance for the day you’re interested in to facilitate making your choice; we spend a lot of time outdoors!)

Q: I’ve seen some tours that are scheduled in advance for particular dates. Do you do that?

A: Yes, in a way. When someone books a tour (unless it’s a private tour) it’s always fun to add a few more adventurous eaters to the group – not to mention the fact that we get the opportunity to taste more dishes when we have more people (although I do like to keep the group size small). You can see if there are any openings available in the “Now Boarding” section of the ethnojunkets page. Subscribers always get email notifications about these.

Q: What will we be eating in Flushing?

A: On this ethnojunket, we’ll choose from a seemingly endless collection of authentic regional delights from all over China: Heilongjiang, Shandong, Henan, Shanghai, Shaanxi, Guangzhou, Hubei, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, and Japan and Taiwan as well. And as if that weren’t enough, we’ll finish with some amazingly rich Chinese influenced American ice cream! If you’re into cooking, we can also check out JMart, a sprawling Asian supermarket. All this within four blocks!

Here are just a few of the delicacies we usually enjoy on this ethnojunket. (Not that I’m trying to tempt you to sign up! 😉)

(Click on any image to view it in mouth-watering high resolution.)

Dim Sum and Dumplings and Buns – oh my!

Dan Tat – Hong Kong Egg Custard Tarts

Xiao Long Bao – Soup Dumplings

I hope you’ll sign up and join us! The cost is $85 per person (cash only, please) and includes a veritable cornucopia of food so bring your appetite: you won’t leave hungry, and you will leave happy!

For more information and to sign up, send me a note in the “Leave a Reply” section at the bottom of this page or write to me directly at rich[at]ethnojunkie[dot]com and I’ll email you with details.

I’m looking forward to introducing you to one of my favorite neighborhoods!

Happy Market Dim Sum Details

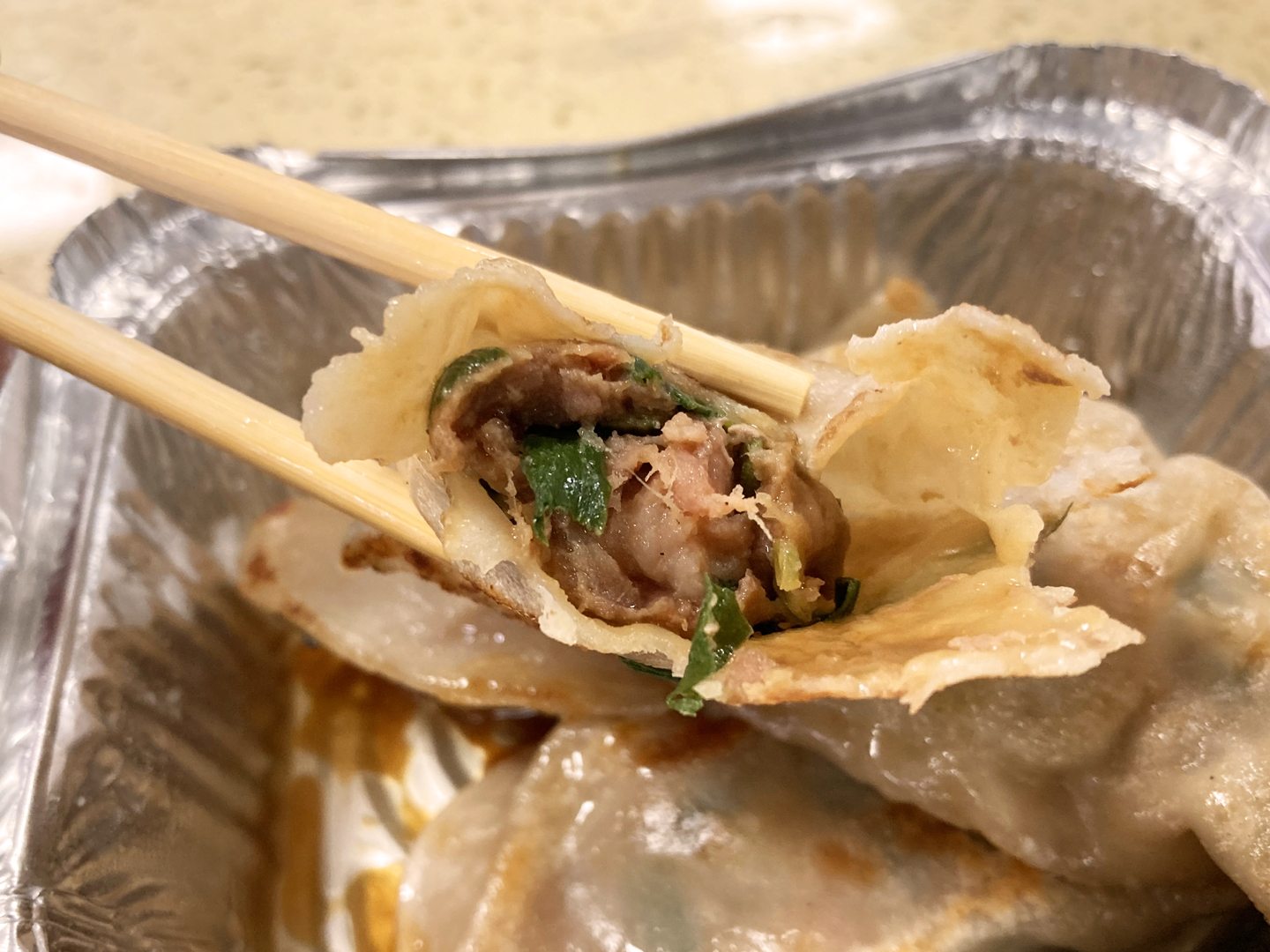

A week ago, I wrote about my visit to the ongoing revitalization of Elmhurst’s Food Court at 8202 45th Ave and promised to show you a close up of some of the dim sum I brought home from Happy Market, so here’s a quick overview of three examples:

(Click on any image to view it in high resolution.)

Beef Ball. Finely pulverized beef, classically served over bean curd skin with Worcestershire sauce on the side just as you’ve probably experienced in your favorite dim sum parlor. Tasty.

Siu Mai (or Shu Mai). A universal favorite executed perfectly here. These are larger than the typical dumpling and it’s clear why: I discovered a whole shrimp in one of these – no, not a baby shrimp, but a seriously good sized specimen! Big hunks of pork as well – the word “hearty” comes to mind. The texture of the filling is robust and chunky (as it should be) and its flavor is excellent.

Chiu Chao Fan Guo (or Teochow Fun Kor or so many other clever Anglicizations). The thick glutinous rice wrapper envelops mushrooms, peanuts, pork, Chinese chives and more; I cut one open to give you an idea of the inner workings. As juicy as it appears in the photo.

All were truly delicious and left me wanting more – and as I mentioned, it’s back on my Ethnic Eats in Elmhurst food tour. And if you’re curious about which of the many dim sum items we actually indulge in, well, you’ll just have to take the tour! 😉

To learn more about my food tours, please check out my Ethnojunkets page and sign up to join in the fun!

Lhasa Liang Fen

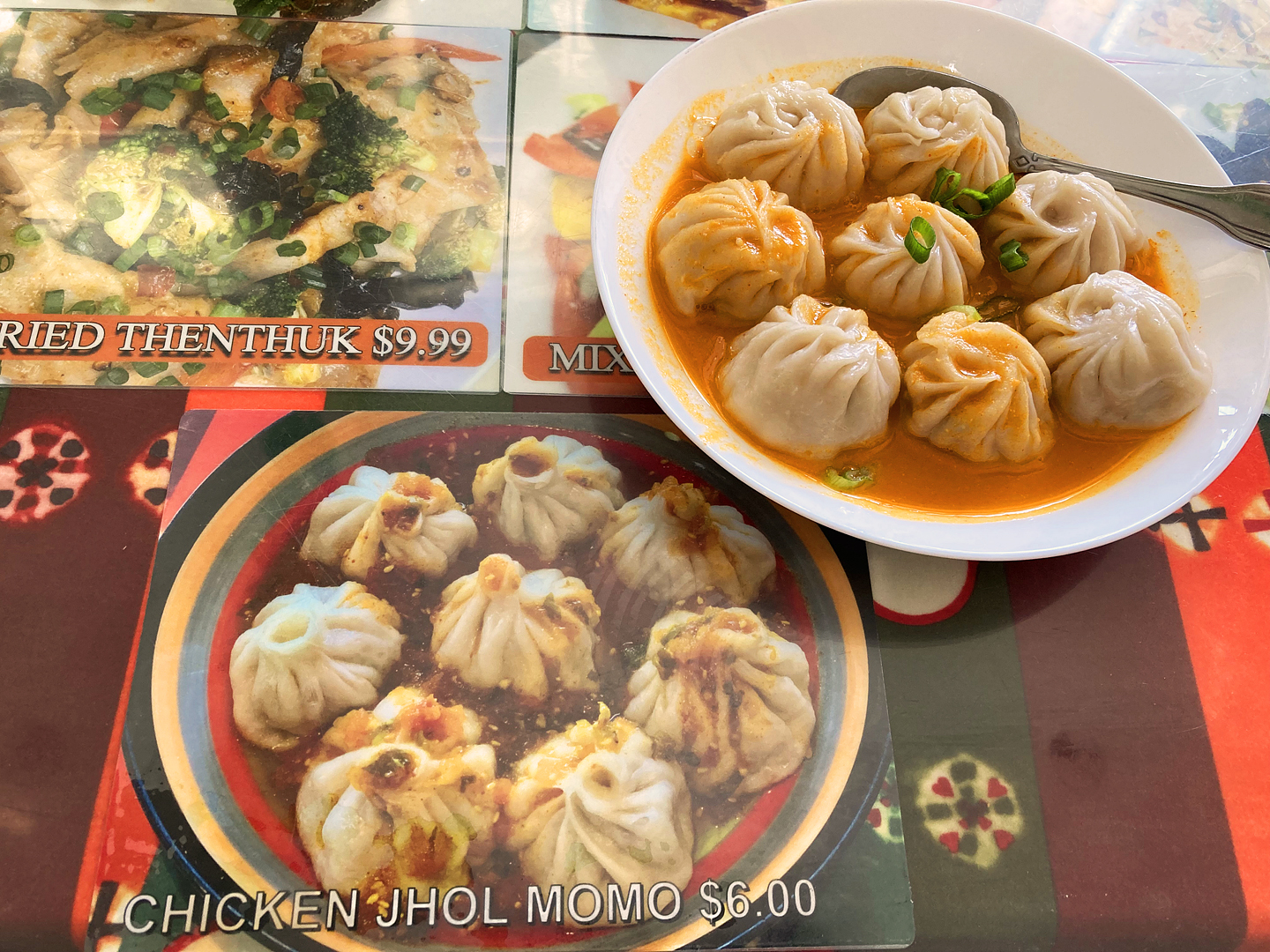

While we’re on the subject of savory Elmhurst food, here’s a shout out to Lhasa Liang Fen, the diminutive restaurant at 80-07 Broadway that serves up Tibetan treats.

(Click on any image to view it in high resolution.)

This is a peak rendition of Chicken Jhol Momo, dumplings that hail from Tibet and Nepal (and Queens, it would seem) that can be fried or steamed like these and are available with a number of fillings; jhol refers to the broth in which they are bathing, and here, it is wonderful. There are some differences between Tibetan and Nepali style momos (more about that in an upcoming post); jhol is a Nepali variation.

Beyond the jhol, the filling in this momo is a cut above others I’ve had in these parts, and that’s saying something: you can’t swing a cat-o’-nine-tails in this neighborhood and not hit a momo joint.

And a big thank you to the lovely staff who provided special treatment for our large group. Now I need to return and seriously eat my way through the rest of their menu!

To learn more about my food tours, please check out my Ethnojunkets page and sign up to join in the fun!

Elmhurst Food Court Redux

(Click on any image to view it in high resolution.)

I did one of my Ethnic Eats In Elmhurst food tours on Sunday. I always arrive early to ensure that the businesses we’ll be visiting are still open (hey, stuff happens), that they’re not out of the goodies we were specifically angling for (that’s happened too), and that my Plan B shelters against inclement weather are available (I’ve been lucky with that one so far).

As I walked past what used to be HK Food Court at 8202 45th Ave, the long shuttered entrance was open – and I smelled food! I tentatively entered and amid significant ongoing construction, like a phoenix rising from the ashes, there were three vendors preparing and displaying their wares in what was something between a dry run and an extremely soft opening. If you go – and you really should – be aware that all the signage hails from the original incarnation and bears no connection to the current vendors (see final photo). But they were indeed open to the public and that’s all the encouragement I needed.

Shortly thereafter, my guests arrived and we checked out the most sprawling of the three. I was told their name would be “Happy Market” and they had been there for only two days. (Timing is everything, right?). In addition to a tempting selection of Cantonese roasted/BBQ ducks, pipa duck, char siu, spareribs, and crispy pig, there was a steamtable set up that I usually associate with “four items plus rice” you’ve probably seen in Chinatowns everywhere, congee, and a considerable array of dim sum.

Everything we tasted was excellent so yes, it’s back on my itinerary. More details to follow, but here are five hastily snapped photos to give you an idea of how things looked; I’ll be doing reports as more vendors populate the new food court.

Having witnessed the demise of so many of our treasured food courts, this brings me joy and gives me hope. Stay tuned….

To learn more about my food tours, please check out my Ethnojunkets page and sign up to join in the fun!

Pata Market – 2022

My first post about Pata Market dates back to July, 2018 and this will be the eighth (!) so you know I’m enamored with the place. I stopped by on a recent excursion to Elmhurst as I was scoping out new options for my Ethnic Eats in Elmhurst food tour – and yes, Pata Market at 81-16 Broadway is always part of the itinerary.

I picked up three snacks. (Actually I picked up seven, but these were arguably the most photogenic of the lot.)

(Click on any image to view it in high resolution.)

I usually think of Hoi Jo as deep fried crabmeat rolls, but the ingredients listed were pork, carrots, bean vermicelli, garlic, salt and pepper. Chewy, salty, crunchy, yummy. (Wasn’t that a song from the late 60s?)

The label read Thai Pancake Stuff which I’ll interpret as Thai stuffed pancake. They’re a layered affair: pandan custard enveloped in a solid crepe and then wrapped in a latticed crepe revealing shreds of sweet egg.

The inner workings, bottom, and top.

Kaw Neaw Moo. Delicious grilled marinated pork on a stick, at once sweet and savory, with perfectly prepared sticky rice. So good.

Check out my Ethnojunkets page and sign up to join in the fun!

More Elmhurst treats to come….

Tindahan

Now that I’ve completed my uber-prudent “post-COVID” exploration of the latest and greatest purveyors of memorable mouthfuls for my Ethnic Eats in Elmhurst food tour, I thought I’d let you in on a few of the places I visited. If you follow me, you know that Zaab Zaab is begging for a return visit. Here’s another new kid on the block – at 81-04 Woodside Avenue to be specific.

Since the cuisine of the Philippines is one of my favorites, I was excited to stumble on this Filipino-owned establishment. Tindahan, the Tagalog word for store, packs its shelves, refrigerator case and freezer with Filipino groceries and prepared food. The focus goes beyond the typical necessities to embrace some specialty items I haven’t found in local pan-Asian markets. (Join me on this ethnojunket and I’ll show you what I found!) A few teasers:

(Click on any image to view it in high resolution.)

Turon. A deep fried lumpia (spring roll) containing a split plantain and a bit of jackfruit for sweetness.

A bibingka is a baked cake usually made with rice flour but cassava or wheat flour is not uncommon. This one is cake-like, soft, sweet and moist within, and topped with potent salted egg and coconut so you get sweet on salty on sweet. Best when warmed, it’s a delicious study in contrasts; get a bit of each in one bite!

Lola’s Empanadas. André told me his grandmother (“lola” in Tagalog) made these so that’s what I’ve been calling them ever since, and they’re outstanding – again, best served warm. Baked, not fried, the sweet dough is filled with pork and chicken, raisins, carrots and peas. I love the fact that they’re doughy inside; I hope that doesn’t change.

Check out my Ethnojunkets page and sign up to join in the fun!

More to come….

Zaab Zaab

(Click on any image to view it in high resolution.)

I had been updating my Ethnic Eats in Elmhurst tour for a few weeks and on one of my initial visits (back on April 16) I spotted Zaab Zaab, the new Isan Thai restaurant at 7604 Woodside Avenue and stopped in for a quick bite. They had only been open for six days and I had my choice of table – but trust me, it’s not going to stay that way; I’m predicting capacity seating. I selected two items from the “Snacks” section of the menu and was happily surprised to receive what I would consider more than just a snack.

I asked about the difference between two contiguous menu items, Nuer Koy and Nam Tok, since both are meat salads. I was told that Nuer Koy was “more rare” so you know which I opted for. Whether it was rare or raw is open for debate but I thought it was great; marinated beef served with fresh hard-to-find herbs, roasted rice powder, chewy pork skin, and spicy as hell, it was as delicious and authentic as any dish I’ve experienced in the neighborhood.

Quail Egg Wonton came with a righteous sweet chili tamarind sauce. My only regret is that I should have asked for an order of sticky rice to accompany the beef. You should too when you go – and I suggest you go soon!

Elmhurst Ethnojunkets Are Back!

Onward and upward!

I resumed Exploring Eastern European Food in Little Odessa about a month ago (a big thank you to all my guests!) and now Ethnic Eats in Elmhurst is joining the lineup; Flushing and Bay Ridge are just around the corner.

Ethnojunkets FAQ:

Q: What’s an ethnojunket anyway?

A: An ethnojunket is a food-focused walking tour through one of New York City’s many ethnic enclaves; my mission is to introduce you to some delicious, accessible, international treats that you’ve never tasted but soon will never be able to live without.

Q: Which neighborhoods do you cover?

A: My most popular tours are described on the ethnojunkets page but there are always new ones in the works. For the time being, I’m only scheduling Little Odessa and Elmhurst.

Q: When is your next ethnojunket to [fill in the blank: Elmhurst, Little Odessa, Flushing, Little Levant, etc.]?

A: Any day you’d like to go! Simply send me a note in the “Leave a Reply” section below or write to me directly at rich[at]ethnojunkie[dot]com and tell me when you’d like to experience a food adventure and which ethnojunket you’re interested in – I’ll bet we can find a mutually convenient day! (Pro Tip: Check the weather in advance for the day you’re interested in to facilitate making your choice; we spend a lot of time outdoors!)

Q: I’ve seen some tours that are scheduled in advance for particular dates. Do you do that?

A: Yes, in a way. When someone books a tour (unless it’s a private tour) it’s always fun to add a few more adventurous eaters to the group – not to mention the fact that we get the opportunity to taste more dishes when we have more people (although I do like to keep the group size small). You can see if there are any openings available in the “Now Boarding” section of the ethnojunkets page. Subscribers always get email notifications about these.

Q: What will we be eating in Elmhurst?

A: We cover a lot of geography on our Ethnic Eats in Elmhurst adventure! We’ll savor goodies from Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, Nepal, Bangladesh, Taiwan, Japan, Hong Kong, the Philippines, and elsewhere in Southeast Asia and parts of China. And if you’re into cooking, we can explore a large Pan-Asian supermarket along the way.

Here are just a few of the delicacies we usually enjoy on this ethnojunket. (Not that I’m trying to tempt you to sign up! 😉)

(Click on any image to view it in mouth-watering high resolution.)

Thai Pork & Peanut Dumplings

I hope you’ll sign up and join us! The cost is $85 per person (cash only, please) and includes a veritable cornucopia of food so bring your appetite: you won’t leave hungry, and you will leave happy!

For more information and to sign up, send me a note in the “Leave a Reply” section at the bottom of this page or write to me directly at rich[at]ethnojunkie[dot]com and I’ll email you with details.

I’m looking forward to introducing you to one of my favorite neighborhoods!